In a time when we are needing to re-focus on values and principles over processes and tools, we tend to forget that in order to carve a sense of “we”, we must understand the “I”. I will share in this experience report the specific workshops me and my fellow agile coaches facilitated for a number of teams during a transformation journey, which gave individuals a chance to express their individuality, discover unique skills and powerful shared values, and the ability to leverage these for incredible outcomes as a high performing team. I have been leveraging these lessons learnt and activities in my subsequent journeys with teams, and I am confident other coaches, team builders, leaders and facilitators can do the same.

1. INTRODUCTION

As an Agile Coach, one of the greatest challenges I face is bringing teams along a journey that appears to be top-down, even when support exists at a team level. I often busy myself on delivering change, rather than place-holding it. In this context, by focusing on individual teams, down to the individual and their response to change, I felt I was able to create lasting impact. By getting people to really listen to each other, understand each other’s personal and professional values, and their unique preferences of working, we were able to facilitate a true social agreement, one that embedded a high level of trust, collaboration and camaraderie amongst the team and led them quickly from ‘forming’, almost speeding through ‘storming’ to ‘norming’. This provided a more cohesive ‘voice of the team’ for me to work with eventually when embarking on the what and how of the transformation, with any challenges brought forward in the future also being more authentic, respectful and from a place of holding each other accountable and a willingness to make the team succeed.

2. Background

In January of 2020, I started working as a consulting Journey Coach for a large financial services organisation in Singapore. At the time, the division I was consulting for was undergoing an Agile transformation, with the intent of identifying end-to-end Client Journey streams, with teams within the journey being spun up to support clients in various elements of their relationship with the organisation, keeping their end-to-end journey in mind.

As a Journey Coach, I had 3 types of services to perform:

One was to train and coach teams and individuals in agile ways of working, with specific focus on techniques and frameworks, such as Scrum, Kanban, Scrum of Scrums, Product Ownership, Scrum Mastery, User Story Mapping, Delivery Planning and Portfolio Management, A3 Problem Solving, and Dynamic Work Design.

One was to coach the enabling teams for these teams, i.e. the relationship managers, customer representatives, experience designers, business stakeholders and sponsors who formed the management and leadership for the individual teams, in agile ways of leadership.

One was to support the capability development of the organisation, by co-developing with other consultants, trainers and professionals, a number of academy programs designed to train and upskill Scrum Masters and Product Owners within the organisation.

A great benefit of having this amalgamation of services to perform was that I was able to observe the many interdependencies between new-to-agile teams, leadership styles, and the learning environment within an organisation. It was only after 3 months of coaching teams and leaders, of training budding Scrum Masters in the organisation, that I started to be able to identify more bespoke ways of enabling the people I was interacting with.

3. Your Story

At around the 3-month mark of this engagement, I was assigned to begin coaching a group of teams (let’s call them the Avengers) to be a part of a new Client Journey. By this time Covid-19 had put Singapore and Malaysia into full lockdown, and the team members, who were split 30/70 between Singapore and Malaysia, were all working from home. They had, pre-Covid, been able to cross the border at least once a month to meet their colleagues or clients. While a few of them had worked with each other in the past, they were mostly unfamiliar with each other except perhaps by name, and had almost only worked on their individual portfolio of work supporting clients in customer-facing roles. They had not had to collaborate much or work as a team before, certainly not with team targets, and were quite new to the concept of ‘agile’ being in traditional client-supporting environments.

As per the recommended approach from the transformation committee, the first few steps to onboard new teams were to take them through a LOT of training, introducing them to the concepts of Agile, client journeys, Scrum, A3 problem solving and Dynamic Work Design. The expectation was that communicating these concepts as well as the vision of the organisation working in client journeys, would help these teams understand the “why” of the transformation. These trainings had been relatively successfully translated onto digital platforms, and teams were given a number of weeks to complete the relevant modules online, as they had to continue on their client-facing business-as-usual (BAU) work simultaneously. It became apparent fairly quickly however, that one-way online training was not that ‘sticky’, and a fellow journey coach and I decided to organise weekly Q&A sessions that the teams could attend after completing specific modules, so that we could discuss concerns, clarify questions and deepen understanding with practical application. This proved quite successful at creating ‘stickiness’ and buy-in, and we bolstered the experiment by having short team-building or ice-breaker activities at the beginning of each Q&A session, in attempts to bring the individuals closer together as a team, albeit remotely.

3.1 Challenges

My fellow coaches and I had begun to sense that all the teams that we were supporting were really struggling to ‘form’, given the pressures of BAU which was also undergoing massive change in the remote world, the overload of all the new Agile jargon, the added expectations of beginning ‘client journey work’ ASAP from the sponsors of those client journeys, not to mention the personal challenges of being in the midst of a pandemic. We diverted our focus as much as possible to support team building activities, however, in light of the “busyness”, the overwhelming screen fatigue, and pressure from stakeholders to focus on delivery, we must admit to have ended up prioritising working on the ‘what’ and ‘how’ whenever possible.

In the case of my teams, the Avengers, the “what” involved training and mentoring the two Product Owners in their role, involved me understanding their clients and their work, and then helping them map out their work with tools and frameworks which would let them identify, prioritise and select the initiatives best suited to experimentation and delivery in sprints. The “how” in my case involved training and mentoring the Scrum Masters and the team members in planning and facilitating sprints and Scrum events, which would allow them to make incremental advances on designing, developing and running the selected experiments in sprints.

It was April 2020 when we kicked off our first sprint, and immediately we realised we had all cornered ourselves into ‘getting stuff moving’. We were planning and re-planning every other day, with very little progress being made on the actual experiment, given that the team members could only dedicate about 30% of their team to ‘client journey work’. We recognised that the context switch between the sprint deliverables and BAU was a huge impediment to the effectiveness of the transition, but even as coaches and consultants we were unable to push back on stakeholders and sponsors to ask for the team members to be dedicated to one or the other.

While my fellow coaches and I continued to work closely with leaders, attempting to gain their understanding of the need of dedicated and stable teams, we were struggling now with degenerating levels of engagement within the teams, who were not seeing any ‘magic’ in this way of working—but simply a lot of ‘things to do’ and ‘even more meetings’. In fairness, the Avengers were a highly optimistic and positive team, never complaining or showing frustration at the processes, and always eager to try something else in the hopes of having an impact or seeing success. But we were seeing individuals work to burnout, swap teams or roles, or quietly express disappointment during retrospectives. In hindsight, I consider myself fortunate that I was working with such an energetic and positive group of people, because anything else would certainly have been negatively contagious and even harder to resolve.

3.2 What you did

Serendipity hit at this time, when an experienced leadership coach at the organisation and I were discussing our current challenges, and she asked with kind curiosity whether we had a team charter in place. I was taken aback and kicked myself a little at having forgotten this crucial step in team formation, and said as much to her. We continued down this train of thought and she shared the kinds of formation activities she had facilitated in the past, as I am always hungry to learn more about my trade from others. We agreed that it would be beneficial to facilitate a values-based team-formation workshop for the Avengers, and she offered to help me design the workshop and co-facilitate it as well, the added benefit being that she was a coach from a non-technology or Agile background, and could potentially create a safer space for the new-to-agile Avengers team to share within.

Given our remote working environment, we spent a few hours over the course of a week planning and designing the workshop, to be facilitated using the organisation’s internal digital collaboration tool, iObeya. We knew we needed to have as much face-to-face interaction as possible, however video calls were challenging within the organisation at the time as very few tools or people were approved to host video calls and/or share screens on internal networks. We were able to escalate this challenge and received access and permission to use Bluejeans, with officially approved internal accounts belonging to two internal employees. My next challenge was getting buy-in from the team and stakeholders for the time required to run this activity, which we knew would take at least 4 hours to really create the space for discussion, connection and learning. I was unable to receive a dedicated morning or afternoon for all the team members to be away from their very variable client-facing schedules, and instead opted for two 2-hour sessions. Feeding this back into the workshop, we re-planned how we would facilitate the activity. Below is our initial agenda and format for the workshop. We decided we would facilitate this with the Avengers as an experiment, and share the outcomes with other Client Journey teams, along with any feedback and improvements, given our observation of similar challenges in other teams.

Around this time, I was reading about Ken Wilber’s Integral Theory [Wilber], and in discussing this with my leadership coach colleague, we concluded that leaders of change often need to be reminded to focus on the “I”, in order to bring about change in the “We”. My colleague and I therefore decided our session would zoom in on the “I” for the team members, before leveraging that for the “We” for the team. The participants would then be able to identify the relevant “It” and “Its” to enable the “I/We” which would form the basis for the team charter/working agreement, which would be the intended ultimate outcome for the session.

3.3 The Experiments

3.3.1 The First Workshop

My Values

Step 1: Opening, intent, agenda setting, creating conditions for safety & kindness.

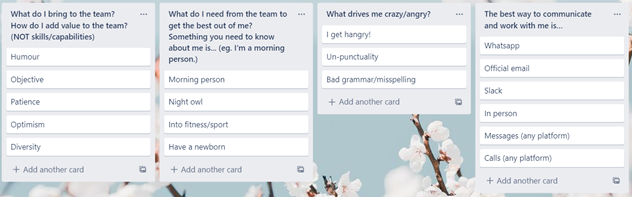

Step 2: Ask participants to silently reflect and answer the following questions using post-it notes on the digital whiteboard in the relevant columns. Timebox: 15min

- A personal value that is core to me is…

- A value I hold core to me in the workplace is…

- The best way to communicate with me is…

- The worst way to communicate with me is…

- At home I like to….

- My professional expertise is…

- The strengths I bring to this team are….

Step 3: Once the timebox expires, facilitate the sharing of what was written, by each team member. Create the space for humour, for lack of judgment, and ensuring responses aren’t rushed through or interrupted. Allow others to relate or comment, with kindness.

Step 4: Wrap-up and close, thank participants, explain what session 2 will involve, encourage reflection on what was shared before that session. The digital board remains open to the whole team to access, however restricted access to anyone outside the team.

Figure 1. Sample Session 1 Board

3.3.2 Lessons Learned

It is incredibly important to stress that this is a get-to-know-you activity, and that as experienced coaches we need participants to trust that this is, and will be, beneficial to them. In a workplace that has a culture of deprioritising ‘unproductive’ work, it is on the coaches and facilitators to lead by example and show comfort and confidence in taking the time for everyone to reflect and to share.

An interesting observation was that the Avengers had 15 team members, and the size had already been a challenge in organising delivery activities and workshops. In this instance the size was a challenge to ensuring that all the team members got to share their reflections and learn from each other and not feel rushed, and was an interesting reminder that Scrum teams are recommended to have less than 9 members specifically in order to not create siloes of conversations or miscommunication. It made us realise how, outside of this workshop and especially in the remote world, this ‘large’ team was likely suffering from incomplete communication amongst themselves and struggling to plan effectively, let alone connecting with everyone on the team at all times. This was another fundamental ‘aha’ moment for me as a coach, and became immediately one of the most important pieces of feedback I provided to the transformation committee in terms of how we ‘assign’ and ‘create’ client journey teams. Sponsors had assumed that at 30% capacity it ‘only made sense’ that a larger team was necessary to ‘get things done’; and I now had first-hand evidence of why such a link of thinking was a logical fallacy. I used this data to paint a simple and obvious picture to sponsors in the future: Would you rather pay for 20 people to finish writing a paragraph over the course of a day, or for 5 of them to spend the day getting an entire essay to ‘Done’? In addition to the cognitive load of context switching, a lack of cohesion and alignment in what people were intending to achieve were significant added barriers to achieving the desired outcomes or even outputs for any group of people.

Despite many of the team members having met each other before, understanding their colleagues’ personal and professional values was a completely new experience for all of them. There was cause for many ‘aha’ moments and sobering moments as every team member shared what kinds of communication worked for them, what didn’t, and their whys. This was really the first time anyone on the team had really looked at “who” they were working with. Assuming that the same ways of working, or that the same motivators for work, would create conditions for high performance was nothing short of ludicrous. More importantly, rather than a coach recommending different tactics, having the space to get to know each other created room for the team members themselves to craft ways to help each other collaborate and be more effective.

We were really encouraged by the openness of the Avengers in their sharing, and the difference it seemed to make in the team’s energy levels immediately after the session. Daily scrums felt a lot more cohesive over the next week, and everyone was looking forward to what session 2 would bring, which was scheduled for a week after the first.

3.3.3 The Second Workshop

Our Values

Step 1: Opening, intent, agenda setting, creating conditions for safety & kindness.

Step 2: Explain what a working agreement/social charter is, and what it is used for

Step 3: In breakout groups, answer the following questions on the digital board under the relevant columns. Each breakout group answers a different question. Timebox: 20min

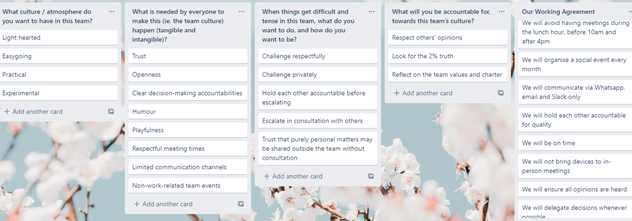

- What culture / atmosphere do you want to have in this team?

- What is needed by everyone to make this happen (tangible and intangible)?

- When things get difficult in this team, what do you want to do?

Step 4: As a whole group, discuss and align expectations from each other. Use the space for the Working Agreement to start jotting down items that come up as ways of working together for the team. The facilitator/coach can guide the conversation in necessary ways, such as reminding participants of the intent of working agreements, to ensure appropriate and insightful ideas are captured.

Figure 2. Sample Session 2 Board

3.3.4 Lessons Learned

It was really useful to have the columns for session 2 right next to all the columns and post-it notes from the previous session, so that participants were able to reflect on each other’s values and thoughts at the same time as crafting their team identity.

While some time for the insights of session 1 to sink in was helpful, a week between sessions was perhaps too long, in that people needed time to go over the outcomes of that session a number of times to remember what had been shared. Our guess was that a maximum of 3 days between sessions would have been the ideal balance.

We needed to rotate the breakout groups to answer each question, i.e., have 3 rounds of brainstorming, in order to get more opinions on page and also to ensure all opinions are reflected and a more cohesive ‘team voice’ is heard.

4. Results

The conclusion of these sessions was nothing short of a resounding success. The Scrum Masters and team members were armed with a unique and honest working agreement, which they visualised and were coached to reflect on and continue to adapt, as needed, at retrospectives. At town halls and other community events, the team members spoke up and proactively shared how much they had valued the time to connect and share, and how it made a significant difference to the desire of engaging in the ‘client journey work’ as they had begun to call it. As their coach, I found facilitating workshops and planning to be a significantly improved experience, with the members of the team able and eager to collaborate on work much more easily, take on shared responsibilities, make more effective use of their time, and most impressively, hold each other accountable to their commitments and to their working agreement.

The feedback from within the team and those who were observing the shift was positive enough that other coaches and teams contacted me and my colleague to facilitate similar sessions for their teams. We decided not just to facilitate but also to enable other coaches to do so, and therefore wrote a facilitation guide (see Appendix A), while also asking coaches to observe any we facilitated. The more teams that experienced the benefits of this activity, the greater the demand for us to facilitate these grew. Each session provided deeper understanding and insight into how the sessions needed to be improved or modified for other teams, and the guide was updated and refined accordingly.

5. Outcomes

The Avengers launched 2 customer-facing experiments within 2 sprints of formulating their working agreement. Other teams reported similar jumps in creativity and eagerness to innovate.

The Avengers split their team into two, with separate product backlogs to work from, although they had the same two Product Owners. While there remained room for improvement in their setup, this small change made a significant difference to the levels of engagement and ability to estimate effort and complete activities. This was a choice that came from within the team rather than one I suggested. And as disappointing as it was for many to let go of the ties they had created, they recognised it was for the greater good of the customer. My role in this instance was simply to ensure they took the time to set new Team Charters in place, and we only ran an hour-long session to draft a new Working Agreement for each team.

Retrospective discussions were more values-based, and I found it easier to facilitate the discovery of unambiguous and actionable process improvements at the end of each. We made changes to the digital tools we used, our meeting times, got more involved in recruitment, and invested in learning and development for the Scrum Masters, ultimately making them the first to become fully dedicated to client journey teams.

The Avengers never began a conversation about performance based on “velocity” or similar metrics, and therefore were rarely held accountable to the same. Instead, we focused on current-value metrics such as Cycle Time and on our ability to innovate, e.g., our Experiments per Month. Other teams at the same time remained beholden to more classic (and ultimately harmful) success metrics such as velocity and features released, with the Team Values workshops acting as stepping stones for them to feel the need to challenge these or feeling even more disengaged when failing to succeed in doing so. For an organisation that was taking ‘data-driven’ conversation quite seriously, it was quite powerful to have metrics tailored to the outcomes for the team and product, focusing on customer outcomes and not productivity, as opposed to teams who were either beholden to output measures and KPIs, or still struggling to challenge them.

These outcomes confirm that:

- People need to have common objectives and shared goals to see themselves as a team

- Psychological safety is key for having a good foundation for collaboration

- Autonomy, mastery and purpose remain the true motivators for high performance in our working lives, more than reward, recognition, or reprimand [Pink]

- Goodheart’s Law: When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure [Strathern].

6. Reflections

Over the 8 months that I coached and trained teams at this financial services organisation in Singapore, I had consulted on a large number and variety of initiatives and projects. It fascinated me then, as it does to this day, that in all that time this team-building activity created some of the greatest impact on the people and the performance of teams across the organisation. As I reflected on this a few months later, I came to the realisation that even before embarking on the Why, let alone the What and How of any change, what we had needed, and forgotten, to do is to take a good look at the Who—the people who would be the drivers of that change. The right people, working together, to their strengths, knowing each other’s challenges, strengths and values, empowered and enabled to help each other in the right ways, feeling heard, being seen, and holding each other to account to their shared commitments at all times—that is the recipe for success for a high performing team.

Earlier this year I read Jim Collins’ Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap, and Others Don’t [Collins] which came to the well-researched conclusion that in order to foster high performing, growth mindset organisations, the organisation needs to hire and retain the “right” people—the Who. Sometimes, that calls for leaders, managers, coaches and team members to say “no” to people, respectfully. I have since then reminded myself of this with every client I work with, and am always mindful to facilitate values-based team building and working agreement workshops whenever I begin coaching a team, and to teach these lessons learnt to other coaches I meet. This experience report, and the facilitator’s guide that accompanies it, is my contribution to one of many things I believe we can do as coaches to inspire this kind of change.

7. Acknowledgements

My sincerest thanks go to Tushar Somaiya and Sharon Lim, my colleagues and co-creators in this experience, for their wisdom, guidance, confidence and support throughout, and for allowing me to share our journey. To every team member and coach who were curious and accepting of our experiments. And to Niels Harre, my shepherd, for your time, your keen eyes, your guidance and positivity in crafting this report.

REFERENCES

[Collins] Collins, Jim, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don’t. Harper Collins, 2001.

[Wilber] Wilber, Ken, The Spectrum of Consciousness. Quest Books, 1993.

[Pink] Pink, Daniel, Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Riverhead Books, 2011.

[Strathern] Strathern, Marilyn, “Improving ratings’: audit in the British University system”, European Review. John Wiley & Sons, 1997.