Managing Cross-Cultural Communication Barriers

As teams become more culturally diverse, miscommunications are more common. Expectations and behavioral nuances differ by country, making it difficult to know what is really being said. Understanding the differences can help a team find common ground and work toward success.

As teams become more culturally diverse, miscommunications are more common. Expectations and behavioral nuances differ by country, making it difficult to know what is really being said. Understanding the differences can help a team find common ground and work toward success.

Toptal Research

If history tells us anything, trends in remote work will continue to make our teams more diverse and multicultural. With that comes a complex landscape to navigate, one with possible missteps and misinterpretations around every corner. Cross-cultural communication in the workplace takes time to understand, but the leaders who understand the differences between countries can shape an organizational culture around what each person needs to be productive and innovative.

Researchers have been curious about the commonalities and dissonances between cultures for a long time. A few frameworks have emerged that provide a way to measure characteristics of countries around the world. They also present cultural nuances you need to know to effectively manage a cross-cultural team.

Although they may be generalizations and aren’t meant to label a group of people, these frameworks are a good place to start in better articulating differences. They shed light on communicating effectively, providing structure for a team, and building professional relationships. Overcoming cross-cultural communication barriers requires a systematic and empathetic approach.

Navigating Different Communication Styles

The nuances of communication are prevalent in all kinds of relationships, but the conversations among team members are particularly critical. A leader of a multicultural team has the challenge of understanding differences between cultures in order to create an effective team. One useful tool in approaching this is Erin Meyer’s Culture Map. She built a framework for understanding the characteristics of communication in countries around the world. Along with other sources of research, deeper patterns emerge that point toward a better way of communicating.

Clarity and Ambiguity in Verbal Communication

Erin Meyer determines the primary difference in communication styles by assessing the acknowledgment of context. In any given society, there is a set of understood reference points and common knowledge. This shared context can dictate how explicitly or implicitly someone will communicate.

In a high context society like China or Japan, it’s assumed that there is a large body of shared understanding and common reference points. It’s believed that the people in the room have enough information about a situation to draw a correct conclusion without the need to say it aloud. Other forms of communication, like body language and nonverbal communication, require people to read between the lines and take in all accounts of context. There’s no need to ensure clarification among a group because each individual simply understands what was implicitly said.

To someone from a low context society like the US or Canada, this would seem rather unsettling. With so much left unsaid, there’s more room for misinterpretation. A low level of context implies that there is little shared understanding and few common reference points. In order to get a point across, it must be said literally and, perhaps, repeated for assurance. Meyer explains that people in low context societies “believe that good, effective, professional communication is a communication that is very explicit.”

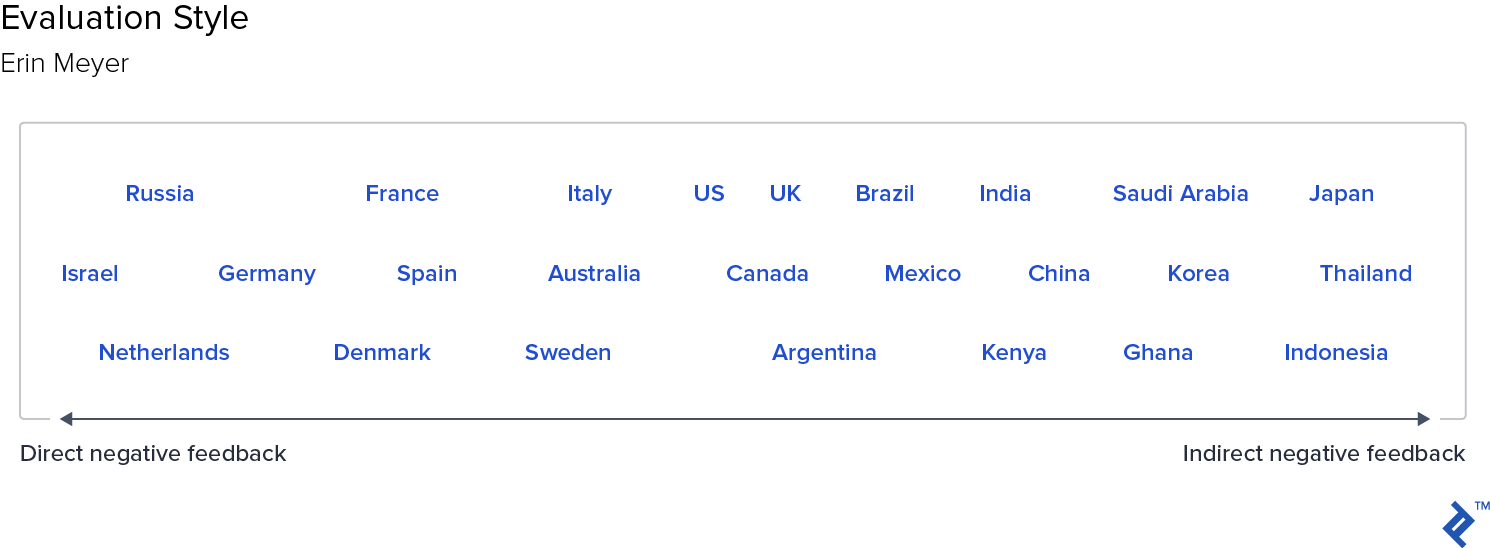

Direct and Indirect Negative Feedback

Someone from a low context society—one who avoids ambiguity—might approach negative feedback in the same way. People from direct cultures are prone to strip away unnecessary pieces of feedback and get straight to the point, no matter how blunt it may be. There’s often little attempt to soften any criticism and instead, these types of cultures use “upgraders” to ensure clarity.

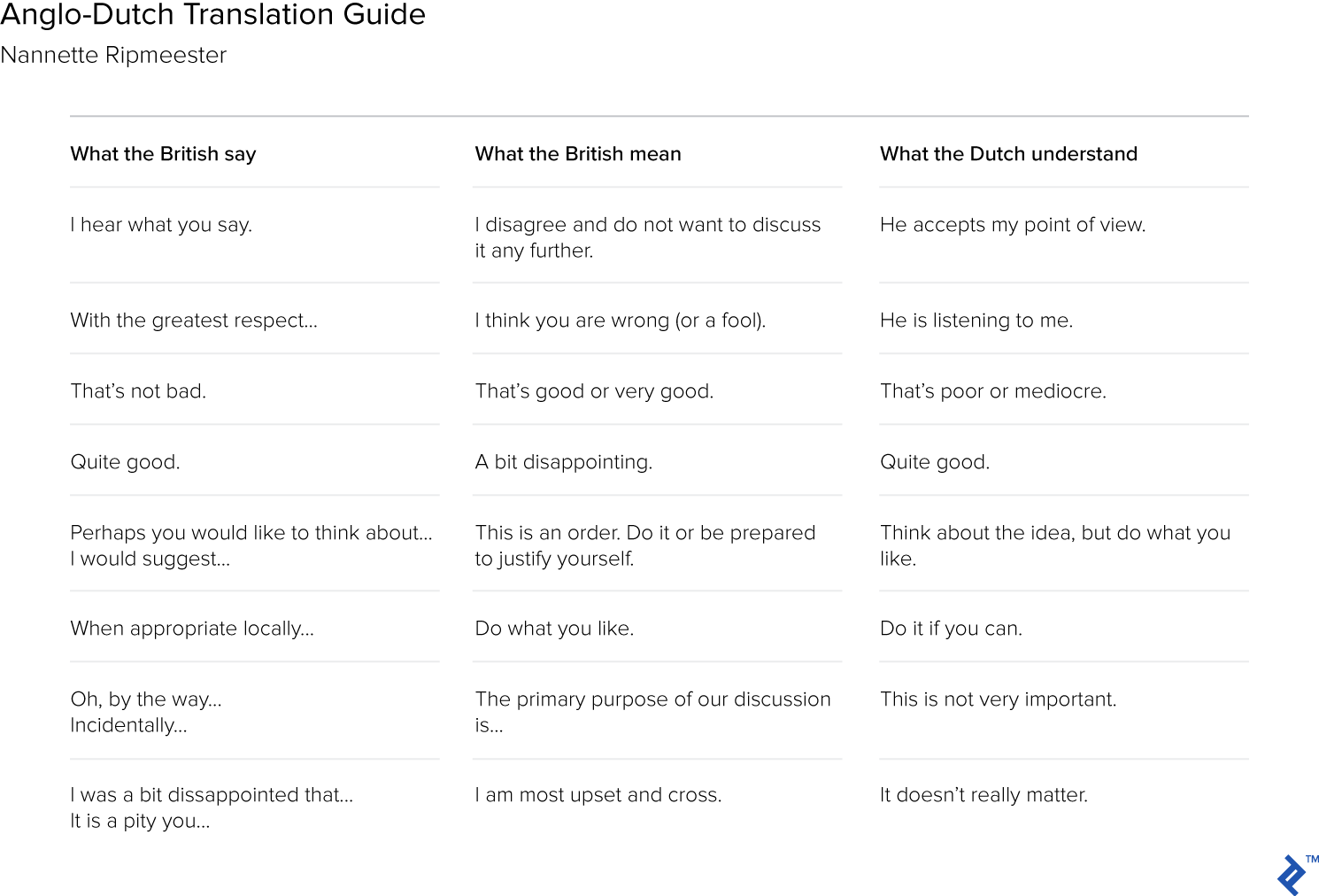

Upgraders are absolute descriptors that eliminate the chance of misinterpretation—e.g., “absolutely” inappropriate or “completely” irresponsible. Downgraders, on the other hand, are used in indirect societies to soften a piece of criticism—e.g., “somewhat” inappropriate or “rather” irresponsible. These qualifying descriptors soften the blow.

The British are known for using a lot of downgraders in phrases like “that’s not bad” when they mean “that’s poor or mediocre.” For someone from a country that speaks directly, like the Netherlands, that phrase communicates something very different. Without knowing whether a colleague uses upgraders or downgraders, a message can easily get lost in the details.

Another factor in differentiating between the two, according to Meyer, is the prioritization of positivity. Indirect cultures will integrate positive feedback in order to be more diplomatic and appreciative. Direct cultures will dive straight into criticism with pure honesty and efficiency. It’s the difference between saying “I disagree with you” and “I’m not sure I understand, can you elaborate?” The implications are the same, but one is straightforward and direct, the other subtle and indirect.

Establishing the Right Amount of Structure

Setting deadlines and putting numerous feedback loops in place is common practice in business. But how much is too much? When do you know you have enough stability and structure? That can depend on who is on the team. Some people prefer certainty and organization while others thrive on spontaneity and flexibility. Knowing who prefers what can overcome cross-cultural communication barriers and unlock a team’s productivity and innovation.

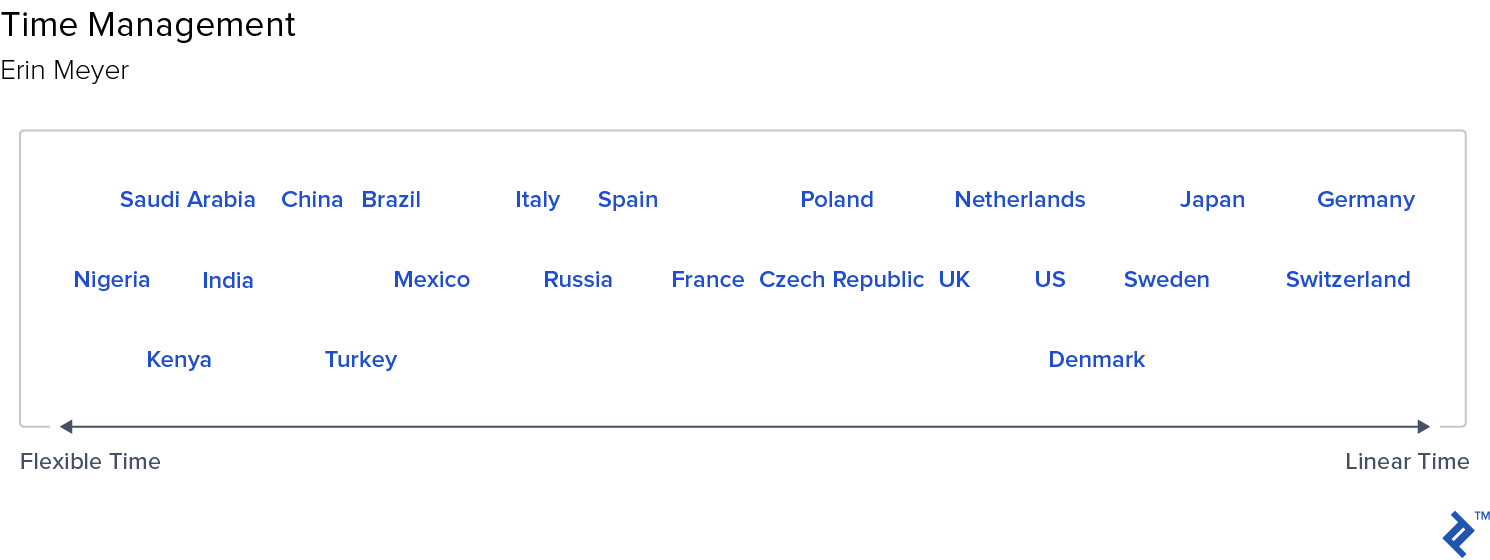

Understanding Time Differently

Some people prefer to stick to a schedule and others are happier without one. Although there are many factors that play into how flexibly someone views time, a country of origin can contribute a lot.

For instance, in the United States, time is money. Linguist Richard Lewis explains that Americans “plan, schedule, organize, pursue action chains, and do one thing at a time” in order to get the most out of time. Their view of time is linear, with an emphasis on promptness and organization. Management consultants Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner describe it as sequential time, where it’s understood that one event follows another.

People on the opposite side of the spectrum see time as synchronous—that the past, present, and future are interwoven and difficult to separate. People from Mexico and Italy are more comfortable with flexibility. When an opportunity arises, they may deviate from a schedule because of the newfound value. Meyer determined that they approach projects in a more fluid manner and deal with interruptions more easily.

So when the Spaniard shows up two hours late to a meeting, it’s because the start time was more of a suggestion. This can be infuriating to someone from Germany who views time linearly and honors promptness. When managing people with different perceptions of time or needs of structure, it’s important to find a middle ground. Set clear deadlines so the team is aligned, but allow space to work in non-linear ways. The presence of structure will be comforting to those thinking linearly. And accepting spontaneity will give other colleagues the freedom to deviate.

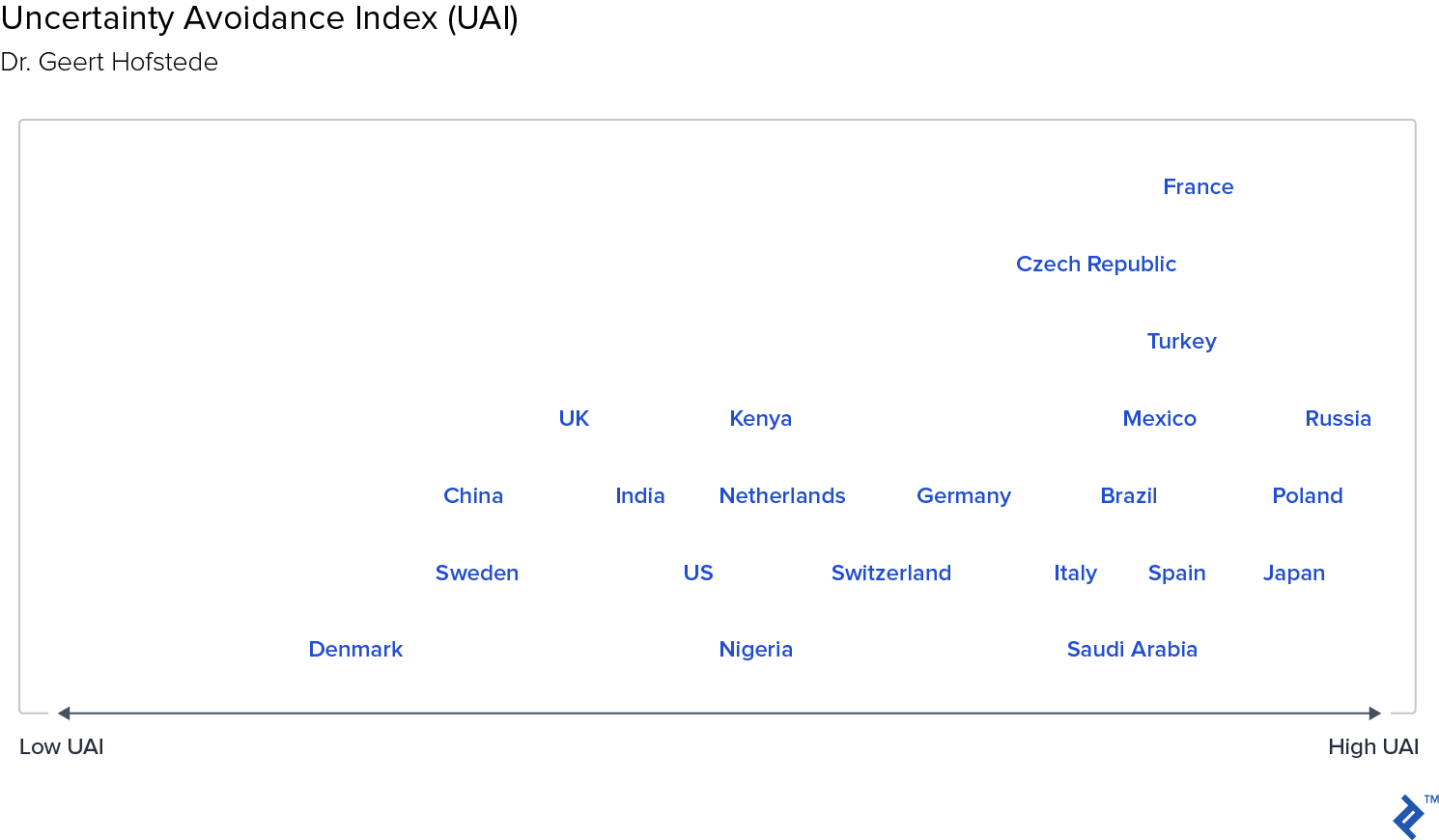

Comfort (or Lack Thereof) with Uncertainty

Dr. Geert Hofstede suggests that acceptance or aversion to structure can be traced back to how comfortable someone is with uncertainty. This is especially prominent when considering various perceptions of the future—and how to get there.

Countries like Russia and Poland have a high tendency to avoid uncertainty. They prefer clear structures and distinct social conventions. Laws, rules, and behavioral norms are in place to maintain security and certainty. The future may never be known, but within these systems, there is some level of control over it.

In contrast, countries with a low uncertainty avoidance are comfortable with few structures and conventions. They are often open to change and innovation—things that have an unclear direction or future outcome. Countries like Denmark and Sweden are not concerned with ambiguity. Cross-cultural communication in the workplace can break down when there is a gap in comfortability among team members.

Leading a team with a mix of high and low levels of uncertainty avoidance requires an empathetic approach. Mediator Ryan O’Connell simplifies it into three steps:

- Consider your own level of comfort with uncertainty. Being self-aware of your own perspective will help to understand others and how they react to you.

- Understand the culture of those in the room. Pay attention to signs of comfort or discomfort in various interactions and situations.

- When it’s clear what the differences are between the perspectives, consider ways to bridge the gap between the two.

Building Professional Relationships

The connections people form in the workplace are based on many factors, including personality and stages of life. However, relationships are also shaped in part by the culture surrounding them. The way in which people regard their colleagues and build trust or personal connections depends on how a society views workplace relationships. If a leader can understand the reasons behind different behaviors, a team culture that is familiar and acceptable to everyone can be fostered.

The Importance of Personal Relationships

Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner’s Seven Cultural Dimensions makes a distinction between specific and diffuse cultures. In a country that is specific, there is a deliberate separation between work and personal lives. “As a result, they believe that relationships don’t have much of an impact on work objectives, and, although good relationships are important, they believe that people can work together without having a good relationship.”

People from a diffuse culture see no boundary between work and personal lives. More than that, they believe good personal relationships are essential to doing good business. Team outings, golf with colleagues, and dinner with clients are all examples of an effort made to establish a good relationship.

Take Japan, a strong diffuse country. A lot of emphasis is put on socializing outside of the office. There isn’t a 9-5 work lifestyle because meetings are often scheduled in the evenings and on the weekends. This is completely acceptable in a culture rooted in trust and loyalty (more on that to come). However, when a British colleague is invited to join for weekend activities, they might view it as an invasion of their personal life. Coming from a “specific” country, they are more likely to keep work at work when they leave the office.

As the leader of a multicultural team, it’s important to make everyone feel comfortable but not forced to participate in strengthening the relationships among colleagues. Organizational consultant Simon Sinek points out that “when people feel safe and protected by the leadership in [an] organization, the natural reaction is to trust and cooperate.” Cross-cultural communication barriers breakdown when people feel like they’re being heard.

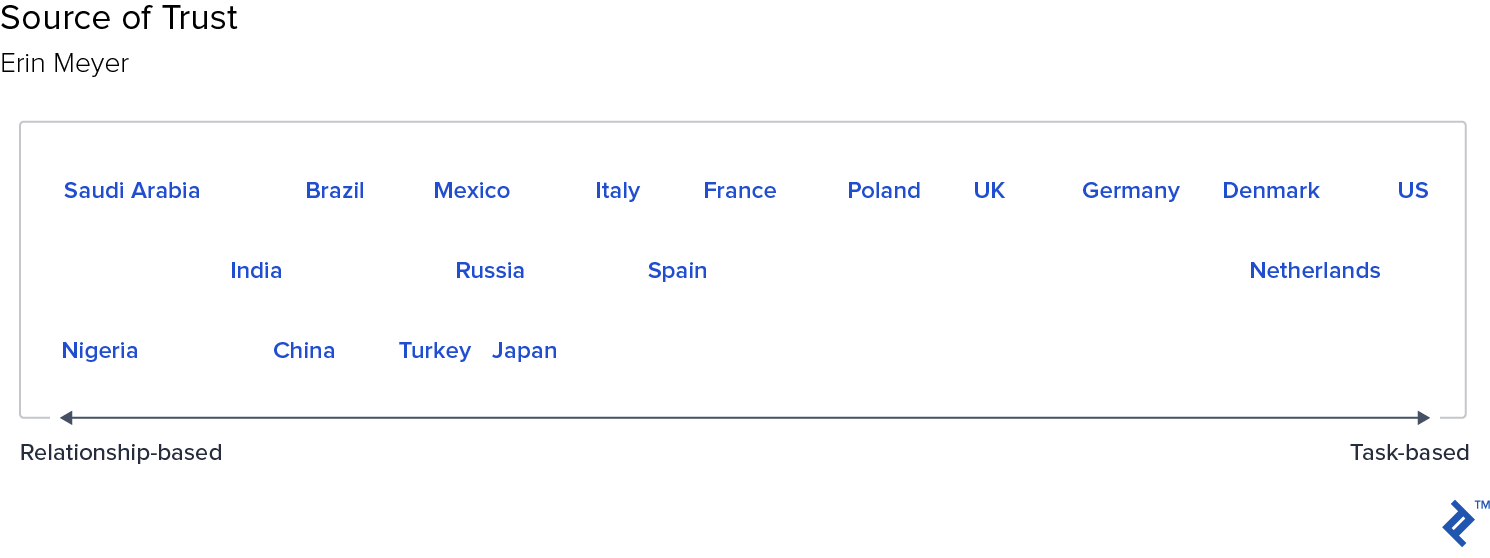

The Source of Trust

Meyer found a different angle on why certain countries favor more personal interactions at work while others prefer the opposite. Building trust within a team comes down to what is perceived to prove someone is trustworthy.

In task-based societies, trust is built through work-based interactions. If someone is trustworthy, it means they are reliable and consistent. Respect of time and personal boundaries can help build mutual trust and loyalty. An American is more likely to work through lunch so no time is wasted in getting the job done—a prime example of a colleague to trust.

Relationship-based societies put much more value on a sense of trust that goes deeper than task delivery. The Chinese call it Guanxi, a relationship that benefits both parties. Meyer explains, “To develop good guanxi, one must build trust from the heart. Forget the deal for a while. Open up personally and make a friend—a real one.” Building a personal rapport allows for colleagues to trust each other. Without it, business suffers.

For leaders building better communication in multicultural teams, this is a good place to start—building trust. Understanding your team’s individual expectations for trustworthy behavior can shape how you cultivate a strong team culture.

The Bottom Line

“Put yourself in their shoes” may seem like a tired phrase, but it is exactly the type of approach needed to build strong communication in multicultural teams. Understanding where someone is from and where they’ve been will help avoid miscommunications of all kinds.

As teams continue to become even more diverse—sometimes completely distributed across continents—being a leader who understands the nuances in cross-cultural communication barriers can manage a team successfully. Cognitive empathy calls for an understanding of another person’s perspective. Compassionate empathy is then used to make decisions with that in mind. Both of these together can set the stage for understanding the unspoken nuances between societies and aligning a team in its own shared culture.