Every once in a while it’s good to take a tool out of its box and find out if it’s still fit for purpose. Maybe even find if it can be used in a new way. I recently did this with the practice of sizing spikes with story points. I’ve experienced a lot of different projects since last revisiting my thinking on this topic. So after doing a little research on current thinking, I updated an old set of slides and presented my position to a group of scrum masters to set the stage for a conversation. My position: Estimating spikes with story points is a vanity metric and teams are better served with time-boxed spikes that are unsized.

While several colleagues came with an abundance of material to support their particular position, no one addressed the points I raised. So it was a wash. My position hasn’t changed appreciably. But I did gain from hearing several arguments for how spikes could be used more effectively if they were to be sized with story points. And perhaps the feedback from this article will further evolve my thinking on the subject.

To begin, I’ll answer the question of “What is a spike?” by accepting the definition from agiledictionary.com:

Spike

A task aimed at answering a question or gathering information, rather than at producing a shippable product. Sometimes a user story is generated that cannot be well estimated until the development team does some actual work to resolve a technical question or a design problem. The solution is to create a “spike,” which is some work whose purpose is to provide the answer or solution.

The phrase “cannot be well estimated” is suggestive. If the work cannot be well estimated than what is the value of estimating it in the first place? Any number placed on the spike is likely to be for the most part arbitrary. Any number greater than zero will therefore arbitrarily inflate the sprint velocity and make it less representative of the value being delivered. It may make the team feel better about their performance, but it tells the stakeholders less about the work remaining. No where can I find a stated purpose of Agile or scrum to be making the team “feel better.” In practice, by masking the amount of value being delivered, the opposite is probably true. The scrum framework ruthlessly exposes all the unhelpful and counterproductive practices and behaviors an unproductive team may be unconsciously perpetuating.

Forty points of genuine value delivered at the end of a sprint is 100% of rubber on the road. Forty points delivered of which 10 are points assigned to one or more spikes is 75% of rubber on the road. The spike points are slippage. If they are left unpointed then it is clear what is happening. A spike here and there isn’t likely to have a significant impact on the velocity trend over, for example, 8 or 10 sprints. One or more spikes per sprint will cause the velocity to sink and suggests a number of corrective actions – actions that may be missed if the velocity is falsely kept at a certain desired or expected value. In other words, pointing spikes hides important information that could very well impact the success of the project. Bad news can inspire better decisions and corrective action. Falsely positive news most often leads to failures of the epic variety.

Consider the following two scenarios.

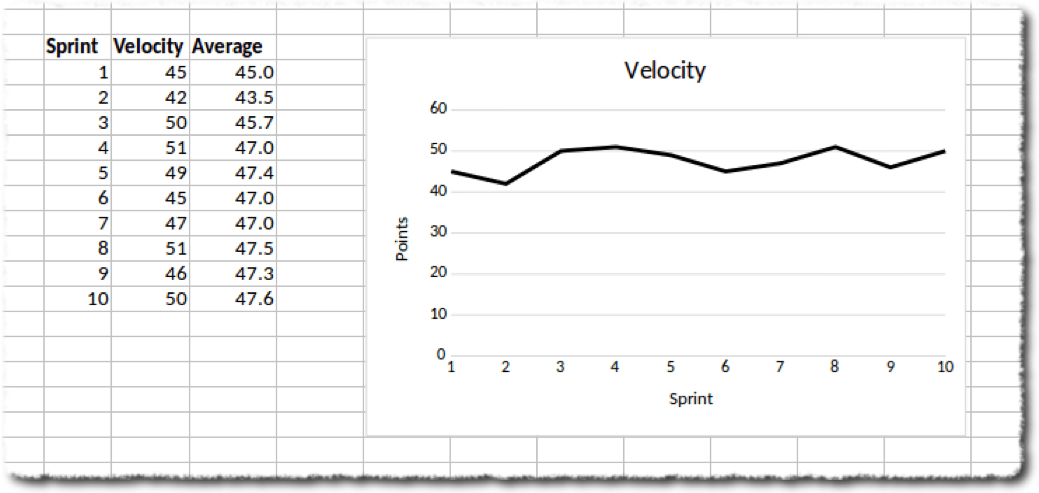

Team A has decided to add story points to their spikes. Immediately they run into several significant challenges related to the design and the technology choices made. So they create a number of spikes to find the answers and make some informed decision. The design and technology struggles continue for the next 10 sprints. Even with the challenges they faced, the team appears to have quickly established a stable velocity.

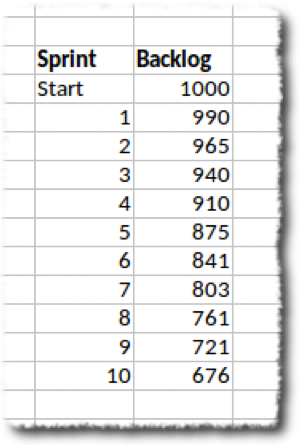

The burndown, however, looks like this:

If the scrum master were to use just the velocity numbers it would appear Team A is going to finish their work in about 14 sprints. This might be true if Team A were to have no more spikes in the remaining sprints. The trend, however, strongly suggests that’s not likely to happen. If a team has been struggling with design and technical issues for 10 sprints, it is unlikely those struggles will suddenly stop at sprint 11 and beyond unless there have been deliberate efforts to mitigate that potential. By pointing spikes and generating a nice-looking velocity chart it is more probable that Team A is unaware of the extent to which they may be underestimating the amount of time to complete items in the backlog.

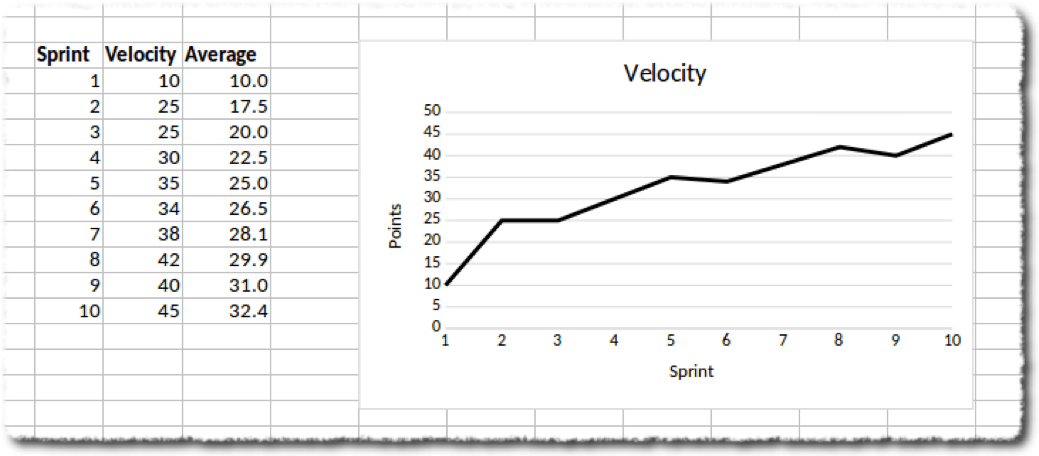

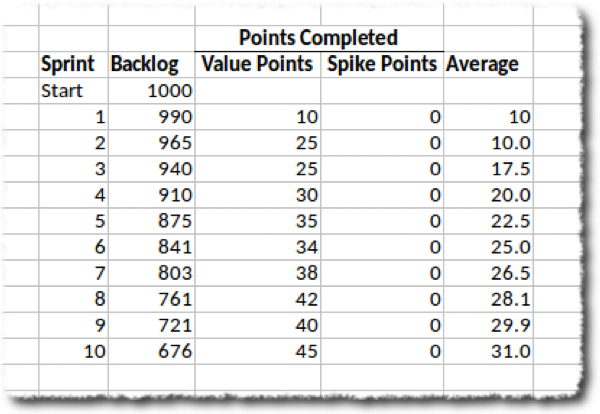

Team B finds themselves in exactly the same situation as Team A. They immediately run into several significant challenges related to the design and the technology choices made and create a number of spikes to find the answers and make some informed decision. However, they decided not to add story points to their spikes. The design and technology struggles continue for the next 10 sprints. The data show that Team B is clearly struggling to establish a stable velocity.

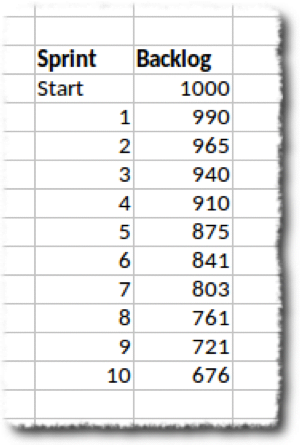

And the burndown looks like this, same as Team A after 10 sprints:

However, it looks like it’s going to take Team B 21 more sprints to complete the work. That they’re struggling isn’t good. That it’s clear they’re struggling is very good. This isn’t apparent with Team A’s velocity chart. Since it’s clear they are struggling it is much easier to start asking questions, find the source of the agony, and make changes that will have a positive impact. It is also much more probably that the changes will be effective because they will have been based on solid information as to what the issues are. Less guess work involved with Team B than with Team A.

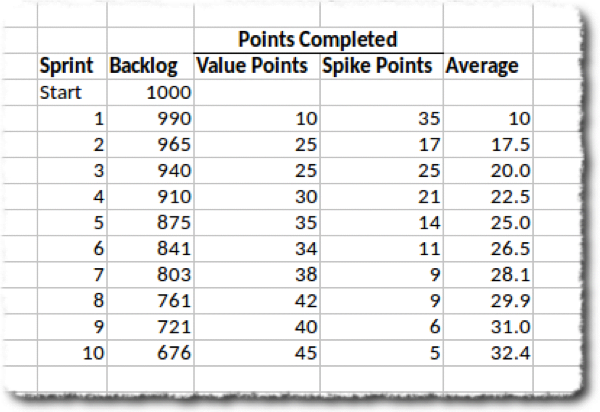

However, any scrum master worth their salt is going to notice that the product backlog burndown doesn’t align with the velocity chart. It isn’t burning down as fast as the velocity chart suggests it should be. So the savvy Team A scrum master starts tracking the burndown of value-add points vs spike points. Doing so might look like the following burndown:

Using the average from the parsed burndown, it is much more likely that Team A will need 21 additional sprints to complete the work. And for Team B?

The picture of the future based on the backlog burndown is a close match to the picture from the velocity data, with about 22 sprints to complete the work.

If you were a product owner, responsible for keeping the customer informed of progress, which set of numbers would you want to base your report on? Would you rather surprise the customer with a “sudden” and extended delay or would you rather communicate openly and accurately?

Summary

Leaving spikes unpointed…

- Increases the probability that performance metrics will reveal problems sooner and thus allow for corrective actions to be taken earlier in a project.

- The team’s velocity and backlog burndown is a more accurate reflection of value actually being created for the customer and therefore allows for greater confidence in any predictions based on the metrics.

I’m interested in hearing your position on whether or not spikes should be estimated with story points (or some other measure.) I’m particularly interested in hearing where my thinking described in this article is in need of updating.