This experience report reflects on various ways of framing organizational change. The way you frame organizational change is likely to influence your thoughts and actions when engaging with a client and an audience. Being aware of various options for your lived-out framing provides you with various means of building rapport with your client, your audience, and yourself.

1. Introduction

“Thomas, we’d like to establish a modern way of working within our organization.”

I advise on organization development and management methods and my response to such a—in my experience, rather typical–statement of intent for organizational change has changed through the years.

My young professional self would interpret such a statement as a carte blanche for organizational change. I would expect the client and the audience to follow the white rabbit—to trust me, to take the plunge and apply new methods, and to welcome their effects. More often than not I would inflict unwanted help on the client and the audience, and organizational change would be prone to a certain degree of futility. Drama would quickly prevail.

My professional self would try to do better. I would try to protect and to serve—to protect the audience from any kind of coercion and to serve the client by following their requests. More often than not I would be at the mercy of both the client and the audience, and organizational change would be prone to a certain degree of arbitrariness. Any impact would quickly vanish.

My experienced professional self tries to sidestep the field of tension between expecting the client and the audience to follow the white rabbit while protecting and serving them. Nowadays, when an organization states its intent to establish a modern way of working, I try to achieve more impact and less drama by keeping a continuous balance of expectations between the client, the audience, and myself.

This experience report tells the story of my way towards this approach. It is dedicated to all consultants who may sometimes relate to the feelings of futility and arbitrariness of organizational change, and who at times might feel like the odds have turned against them.

2. Background

I have been working for several years with various organizations where I have come across a rather vague intention for, understanding of, and marginal commitment to organizational change. In such organizations, I usually deal with the following three groups of people:

- The client are those who fund organizational change and confer my mandate.

- The audience are those who are affected by or contribute to organizational change.

- I myself am the one who advises the client and the audience on organizational change.

My mandate may last from a few months up to one and a half years. Sometimes I manage to talk to the client before I meet the audience, sometimes I take up contact with the audience before I manage to talk to the client, and sometimes I do not manage to talk to the client at all (beyond their initial request).

3. Part I: Follow the White Rabbit

“We’d like to establish a modern way of working within our organization.”

“Sure, no problem! I am aware of various ways and means. I will choose some of them for you and I will show you how to apply them. You will then work in the same modern way as other organizations do.”

As a young professional, I framed organizational change as the introduction of predefined roles, meetings, and processes; using their rate of adoption as a measure of success. I pictured the client as someone who has a problem, the audience as someone who needs help, and myself as someone who is an expert.

Situation 1: I decided to introduce a collaboration framework along with new roles, documents, tools, meetings, and processes. I taught these artifacts and expected the audience to apply them as a part of their everyday work routine. Over time it occurred to me that the framework was thought to be an end in itself while its artifacts did neither serve the client nor the audience.

Situation 2: I decided to introduce new skills for collaborating across teams. I taught these skills and expected the audience to apply them as a part of their everyday work routine. Behavioral patterns revealed that the audience became overburdened with acquiring new skills on top of running their day-to-day business.

Situation 3: I decided to introduce new techniques for collaborating within a team. I taught these techniques and expected the audience to apply them as a part of their everyday work routine. Behavioral patterns revealed that the audience did not, for whatever reasons, apply these techniques and continued to work in the same way they always had.

In all these cases, framing organizational change as the introduction of artifacts did not serve the client, the audience, nor myself in the end. These modern ways of working were decoupled from the client’s needs and were perceived as invasive by the audience. I noticed that a growing sense of futility started to make me doubt my abilities and so I decided to leave this framing behind.

4. Part II: To Protect and to Serve

“We’d like to establish a modern way of working within our organization.”

“Sure, what would you like to do? I am aware of various ways and means. I will suggest some of them to you and will let you decide which to apply. You will then work in your very own and unique modern way.”

As a professional, I framed organizational change as a (metaphorical) open-ended journey; liberated from predefined expectations and responding to options that would emerge along the way. I pictured the client as someone who would recognize where to go, the audience as someone who would know how to get there, and myself as someone who offers travel companionship along the way.

Situation 4: A client expected the audience to work in modern ways and to figure out themselves what these ways might look like. The audience, in turn, awaited instructions. I waited for someone to budge and end this standoff, assuming I would protect the audience by not inflicting help and that I would serve the client by supporting their expectation that the audience would eventually figure out modern ways of working by themselves.

Situation 5: An audience expected freedom of choice for their way of working. The client expected to have a say in choosing their way of working as well. I tried to please both the audience and the client by showing understanding for both.

Situation 6: I decided to support any modern way of working that an audience would come up with. The audience meandered through a variety of suggestions over time. Meanwhile, the client demanded focused progress. I tried to protect the audience from the client’s demand, and, at the same time, I tried to serve the client by supporting their demand.

In all these cases, framing organizational change as an open-ended journey did not serve the client, the audience, nor myself in the end. These modern ways of working did not provide orientation for the client and did not challenge the comfort zone of the audience. I noticed that a growing sense of arbitrariness started to make me doubt my abilities and so I decided to leave this framing behind.

5. Interlude

As you might imagine, both framings provoked tensions in one way or another. Clients would feel stressed because of stalled or purposeless progress, audiences would feel stressed because of too little or too much freedom, and I would feel stressed because I lacked efficacy or influence.

Instead of trying to become better at navigating these tensions, I considered it necessary to reframe my understanding of organizational change once again. Bit by bit, I tried to bring into being a framing that would allow me to

- relate to the context of a client and an audience while keeping a distance,

- act autonomously while making a difference for the client and the audience, and

- consider expectations of the client and the audience while enabling me to divert from them.

6. Part III: More Impact, Less Drama

“We’d like to establish a modern way of working within our organization.”

“Sure, so let us talk about your situation. I will ask you some questions to relate to your context and I will then mirror my thoughts to you. I will advise on an initial adaptive move and, if you agree, we will regularly review its effects and adjust accordingly.”

As an experienced professional I have, for the time being, arrived at framing organizational change as a relation to the context of a client and an audience. Framing organizational change in this way informs me why, when, and where to shift my focus of attention and enables me to explain this to the client, the audience, and myself. I have arrived at this framing after going through realizations that came to my mind after reading and weaving together three key concepts that I learned from three different books.

First, I realized that organizational change can be regarded as a product that should meet the needs of the client, the audience, and myself. Framing organizational change as the introduction of artifacts would fall short of this aspiration as it would primarily serve my own idea of how a modern way of working might look like. This realization was inspired by [1] that illustrates how to align product development using an agile charter.

Second, I realized that organizational change would benefit from a strategy that is plausible for the client, the audience, and myself. Framing organizational change as an open-ended journey would fall short of this aspiration as it would not include a plausible strategy. This realization was inspired by [2] that illustrates how to coherently position yourself using a strategy core. Note that a plausible strategy is not necessarily an adequate strategy.

Third, I realized that organizational change is ongoing work in progress that needs to be continuously shaped by the client, the audience, and myself. Framing organizational change as the introduction of artifacts or as an open-ended journey would fall short of this aspiration as it would only allow for either me or the client and the audience to shape it, respectively. This realization was inspired by [3] that illustrates how to foster an adaptive understanding of a situation using the ladder of inference.

These realizations have changed how I deal with a client, an audience, and myself. I started to adopt the following steps that I recurrently go through when responding to a statement of intend for organizational change. By now, framing organizational change as a relation to context includes for me

- to clarify the context of the client and the audience,

- to start a relation to their context, and

- to maintain a relation to their context even while that context changes.

6.1 Clarifying context

To clarify the context, I start by collecting observations. For example, I might observe that calendars are always packed, that meetings always start late, or that decisions are always postponed. My objective is to collect as many observations as possible and to only collect observations that leave no room for interpretation.

Situation 7: “I noticed that you maintain a prioritized list of pending features for your software product and that you have given one-third of these features the highest priority. Is that correct or am I missing something?”

“You are correct, this is as it is.”

I refrain from any immediate interpretation (“You need to improve on prioritization.”) or judgment (“One-third is too much.”) of such observations. My reasoning is that I want to be able to describe the context of an organization in terms that are unlikely to provoke disagreement and that one cannot argue about. I am aware that any such collection of observations is incomplete. I usually collect a double-digit number of observations and then proceed to the next step.

6.2 Starting a relation to context

To start a relation to context, I consider some of my observations while I ignore others for the time being. For example, I might consider a set of observations that seem to repeat, seem to relate to each other, or seem to contradict each other. Only now I start to interpret the observations that I have selected (“What does this might mean?”) and, based on this interpretation, I start to draw conclusions (“Assuming that my interpretation is correct, what reasonable actions can I take?”)

Situation 8: I noticed that the audience did not share what they were working on and that they did not use any tools to make their work visible (observation). After speaking to some of them, I felt that they were proud in being able to manage their work on their own and that they would consider sharing what they were working on as a cry for help (interpretation). I decided to not push for more transparency for the time being (conclusion).

I aspire to build a few plausible sequences of observations, interpretations, and conclusions. I am aware that my selection of observations, my interpretations, or my conclusions might turn out to be inadequate. That is why I make use of a mechanism that allows me to adjust them over time.

6.3 Maintaining a relation to context

Given that I am operating on an incomplete collection of observations, along with potentially inadequate sequences of selected observations, interpretations, and resulting conclusions, I try to maintain a close relation to the context of the client and the audience.

Situation 9: “I noticed that you maintain a prioritized list of pending features for your software product and that you have given one-third of these features the highest priority. I suppose that means that you need to improve on prioritization, and I suggest that we establish a new way of prioritization in your organization. What do you think?”

“Hm, I don’t know. Have you also noticed that a lot of those features have been pending for over a year?”

“So, you mean that by following my suggestion we would establish a new way of prioritization only to apply it to features that are likely to never get implemented?”

“Yes.”

“Thanks for pointing that out to me. Instead, we might think of new ways to speed up your implementation, or we might think of new ways to identify and dump rather than manage waste in your list of pending features.”

I hold my sequences of observations, interpretations, and conclusions visible while I ask for feedback and even invite criticism. Any feedback or criticism might help me to uncover new observations, or it might lead me to new interpretations or conclusions. When working with an audience I try to apply this method on an almost daily basis. I also apply this method to maintain a relation to context with a client, albeit on a different timescale. About every six weeks I meet with the client and I apply this method to reflect with them on my mandate as well as the adaptive move (along with its effects) that we have previously agreed on. These meetings almost always result in adjustments of my mandate and in a new adaptive move.

Holding my sequences of observations, interpretations, and conclusions visible while encouraging feedback and inviting criticism amounts to single-loop learning with regard to the context of the audience and allows me to improve within the bounds of my current mandate; with regard to the context of the client, it allows me to adjust my mandate and amounts to double-loop learning [4].

6.4 Effects

Switching my framing of organizational change as the introduction of artifacts or as an open-ended journey towards a framing as a relation to context has had noticeable effects on my clients, my audiences, and myself.

Clients have told me that they like to see and to be involved in my line of reasoning when agreeing on my mandate. They seem to appreciate the opportunity to reflect and to influence my mandate based on new observations, interpretations, and conclusions. I can imagine that relating to their context in a structured and flexible way is a welcome diversion from their otherwise hectic working days.

Audiences have told me that being welcome to question and challenge my line of reasoning feels safe and builds trust. They seem to appreciate that they have a say in organizational change. I can image that relating to their context in a transparent and agnostic way is a welcome diversion from otherwise being told what to do.

As for myself, I feel that framing organizational change as a relation to context has increased my sense of self-efficacy. It allows for purposeful work with a client and for impactful work with an audience when responding to a statement of intend for organizational change. (I have written more on self-efficacy in [5].)

7. Insights

This experience report covers a period of several years, which came along with a manifold of insights. Among these, the following personal realization stands out for me.

Organizational change means first and foremost working with, and working on, expectations.

7.1 Focus of attention

I have realized that, in addition to expectations, necessities and behavioral patterns contribute to the context of an organization as well and came up with the following distinction.

- Necessities include all things that inevitably need to change or must not change. For example, a necessity might be to comply with a legal requirement or to response to an existential threat.

- Expectations include all things that people would like to change as well as all things that people would like not to change. For example, people might expect that employee sense of ownership, work productivity, or customer satisfaction should increase. People might have implicit or explicit expectations, or both.

- Behavioral patterns are situations that repeat over time. For example, meetings might follow an entrenched routine or people might exhibit a recurring form of interactions.

I am aware that restricting the context of an organization to necessities, expectations, and behavioral patterns is a simplification. I am also aware that the context of an organization is at no time ascertainable in full.

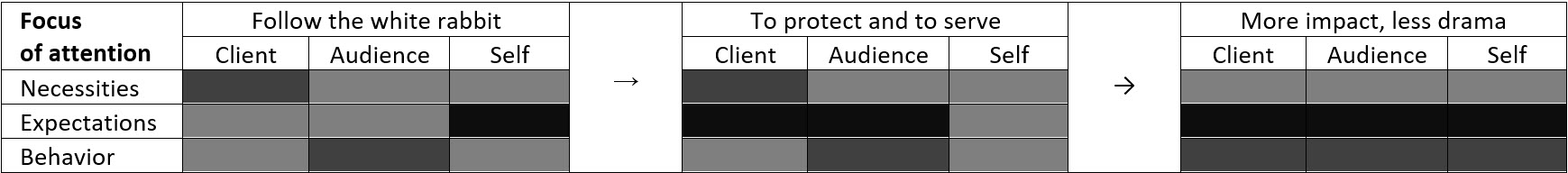

My different framings of organizational change differ by their particular focus of attention towards the client, the audience, and myself. The following figure is a makeshift heat map that shows how I have shifted back and forth my focus of attention between necessities, expectations, and behavioral patterns over time (here, lightly colored cells indicate a subordinate focus while darkly colored cells indicate a main focus).

Figure 1. A visualization of my focus of attention over time

When I expected the client and the audience to follow the white rabbit, my main focus was on meeting my own expectations of what organizational change would look like, and I have subordinated expectations of both the client and the audience. When I tried to protect (the audience) and serve (the client), my main focus was on serving the expectations of the client while protecting the expectations of the audience, and I have subordinated my own expectations.

The figure also reveals the possibly somewhat counterintuitive quirk that I tend to prefer a focus on expectations over a focus on necessities as I have experienced that a client or an audience would quite often—yet not always—present an expectation as a necessity to me. Note that the introductory request (“we’d like to establish a modern way of working within our organization”) states an expectation rather than a necessity.

7.2 Characteristics

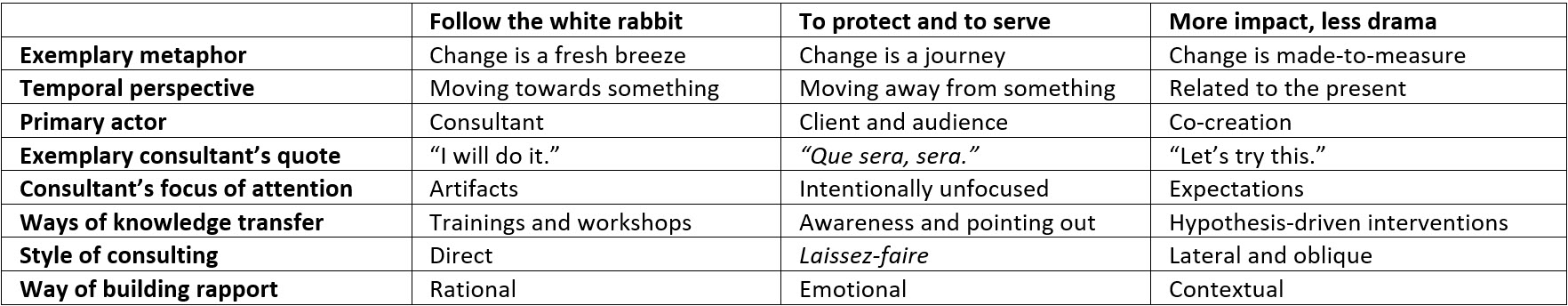

I have tried to convey my way towards framing organizational change as a relation to context in this experience report. To possibly make this rough idea more tangible I offer the following figure that contrasts my lived-out framings by means of various aspects.

Figure 2. Characteristics

Note that these framings do not compete and that they are not mutually exclusive. My attempt at characterizing these framings does not claim to be comprehensive and is not meant to judge any framing.

7.3 Boundaries

I conclude with a few words of caution. Firstly, please be aware that this experience report is subjective and that it is, perhaps less apparent, prone to the cognitive bias system of retrospective coherence. Please be critical of what you have read. Lastly, please remember that this experience report has emerged from working for several years with various organizations with a rather vague intention for, understanding of, and commitment to organizational change. For other organizations, different framings of organizational change may be adequate and may prepare the ground for different effects and experiences.

8. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all people who have given me an opportunity to write or speak about my idea of framing organizational change as a relation to context and whose feedback has enabled me to gradually refine it. A special thanks goes out to Staffan Eriksson for his encouragement to recount my story and for his guidance while shepherding this experience report.

REFERENCES

[1] Larsen, Diana and Nies, Ainsley, Liftoff: Start and Sustain Successful Agile Teams. The Pragmatic Programmers, 2nd edition, 2016

[2] Rumelt, Richard Good strategy, bad strategy: The difference and why it matters. Profile Books, 2011

[3] Noonan, William R. Discussing the undiscussable: A Guide to Overcoming Defensive Routines in the Workplace. Jossey-Bass, 2007

[4] Argyris, Chris and Schön, Donald A. Theory in Practice: Increasing Professional Effectiveness. John Wiley & Sons, 1992

[5] Epping, Thomas “Three Patterns for Self-Efficacy: More Impact, Less Drama” in Proceedings of the European Conference on Pattern Languages of Programs 2020 (EuroPLoP ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 8, 1–5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3424771.3424774