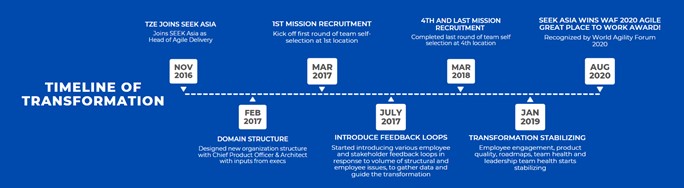

This is the story of a once industry-leading organization that fell into the pitfalls of success: complacency, bureaucracy and aging technology. Through acquisition and merger, it was given the opportunity to be reborn itself as a nimble, agile organization. This report the journey of the leadership team brought together to revitalize, energize and reinvent once mighty giants, with the outcome of being recognized as winners of the World Agility Forum 2020’s Agile Great Place to Work Award.

1 INTRODUCTION

This is a story of two incumbent giants in the East Asia online job recruitment industry. Founded in the late 1990s, Jobstreet.com and JobsDB were titans in the job search space. Their collective success made them household names. Many graduates found their first jobs through these job portals. Jobstreet and JobsDB were eventually acquired and merged into a single entity, named Seek Asia. Its combined presence resulted in business presence in 6 countries across Southeast Asia and Hong Kong. The Product & Technology organization was over 200 strong and spread out across four locations: Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and two locations in Malaysia.

Corporate mergers are inherently challenging. The merger of two rivals is especially precarious. These two organizations were fierce competitors with a presence in overlapping markets and competing products and services. There were two of everything – products, internal systems, teams. To make things worse, there were existing and emerging competitors. At the end of 2016, they had several challenges around people, process, and technology:

- Deployments to production were 1+ deployments per month (excluding support fixes)

- ~25% of support issues did not meet Service Level Agreement (SLA)

- Staff turnover at ~30%

- Employee engagement below 20%

Something had to be done. SEEK Asia embarked on an organizational and cultural transformation. Fast forward to 2020, plenty had changed. As for the efforts? The World Agility Forum 2020 recognized them with the Agile Great Place to Work award.

2 Background

I joined SEEK Asia as the Head of Agile Practice in late 2016. SEEK Asia had already been merged as a corporate entity a year prior, however it was still largely operating as two separate organizations. I had been brough on-board by a mentor of mine, who was the CIO at the time. I fondly recall that during the last interview, the Head of Talent Acquisition asked me a direct question: “Are you sure you want to join? It’s messy here.” I replied with a resounding ‘YES!’ as I was looking for an opportunity to create a local Asian story of a successful agile organization.

My background at that time was in software product development, to meet customer needs through software products and services. I have played numerous roles in agile teams—software engineer, technical lead, delivery manager, designer, product owner and coach. While I did not have prior experience in leading large scale agile transformation, I brought deep experience in developing software products, coaching teams and problem solving.

We had big dreams to revitalize and reinvent SEEK Asia’s product & technology organization, to attain what we knew this organization was capable of. This is my story of how we did this.

3 My Story

My first 90 days were primarily a sensing journey. Being heavily influenced by The First 90 Days (1) I wanted to start engagements well by learning as quickly as possible and forming internal alliances towards shared goals. This is what I learned those first 90 days:

- Decision bottlenecks – Many team members were constantly waiting for decisions to be made by specific subject matter experts or delivery managers.

- Poor line-of-sight to the customer—Teams did not know who they were developing additional features or resolving support cases for. To understand the length of their line-of-sight to the customer, I ran a simple exercise; I would ask a team member Who are you building (or fixing) this for? If they could not answer, I would follow up with Who could I ask? I would approach that person and repeat until I found who the customer was. On average, the line-of-sight was about 4.

- Duplication of responsibilities—Due to the merger, there were two teams responsible for the same user functionality, however, for different brands and platforms.

- Low employee engagement—Many team members did not feel that they were growing in careers and engaged in their work. Key staff were allocated to multiple projects and felt stretched.

- The pace of new value delivered to the market is slow—Deployment frequency was around ~1 deliveries per month, excluding production support fixes. With the threats from faster competitors, we were not responding fast enough to customer and market demands.

- Management turnover—Post-acquisition and merger, long-time managers had left the organization. This had resulted in a management vacuum, broken lines of escalation, and issues left unresolved.

- High workload—There was more work than what we had capacity to do (though isn’t this the same everywhere?).

While there was no shortage of problems, I had to find the appropriate acupuncture points to start shifting the organization. I have learnt through experience that successful changes are those which address the biggest pain points with the least effort. What was a concern for me, however, was what approach to take to maximize our probability of success. I had been part of prior organization transformations, many of which were failures. Some studies have pegged the failure rate at 3 out of 4 transformations fail! (2)

We knew we had to change; we had to embark on a transformation. The dilemma was: How?

3.1 Problems

There was no shortage of issues during my sensing journey. I would either find problems through direct observation or be told of problems when I had my chat sessions with individuals and teams. To make sense of it all, I categorized problems, and sorted them into the following themes:

- The pace of delivery: How quickly can team and team members make good enough decisions, take action and deliver value.

- Employee engagement: How are team members engaged in their work and what is their ability to grow on the job, which directly affects productivity.

- Single organization: The organization was inefficient because of the merger; therefore we had to improve efficiency through de-duplication of roles and responsibilities.

While these were organizational issues, we had one more issue—How will we go about fixing them? As with my leadership peers, we have experience in building up product delivery teams, though none of us had a background in change management and transformation.

Leveraging on our collective product development experience, we approached organizational transformation similarly. We created a vision, laid down our operating values and principles, and leadership working agreement. Our operating values were: customers over profits, one organization, inspect and adapt and people first.

Figure 1. Timeline of our transformation

3.2 Our Approach

3.2.1 Design the New Organization

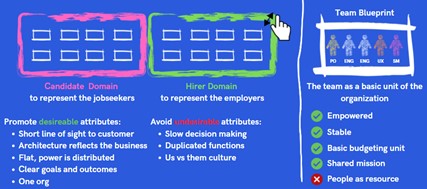

We decided that the first problem to solve was the duplication of teams. To do this, we redesigned the organization. Working with the newly joined Chief Product Officer (CPO) and Lead Architect, we created a portfolio view of the various systems supporting our job seekers and employers and sketched up a simple yet complete customer journey. Guiding us were the following design goals: teams know which customers they are serving, the resulting Product & Technology organization mirrors our business model and our technology architecture reflects our business model (aka Conway’s Law (3)).

Through this we came up with what we called our domain structure, with people in teams and teams in specific customer domains. This model is radically different from our previous structure, which was oriented around the specific component, applications, or projects. With this model, our intention was also to move away from traditional project financing towards value-stream financing with budgets allocated to specific domains, allowing leadership within each domain to have more flexibility in prioritizing investments while keeping to our overall budget positions.

Figure 2. Domain Structure Model & Team Blueprint

Part of designing the new organization structure entailed the introduction of the team blueprint. One of the prevailing issues was that we stretched key individuals across multiple projects, with delivery managers requesting for those people to accelerate or save late projects.

This had the effect of increased burnout, staff resignations, and overarching feelings of lack of professional growth. With the introduction of the team blueprint, the fundamental unit of the organization is a product delivery team comprising a Product Owner, four to six software and test engineers, a designer, and supported by an Agile Delivery Lead and a Data Analyst. Team membership is stable, and people could not be allocated to multiple teams. Work could only be allocated to teams and not individuals.

3.2.2 Reboot the Culture through Mission Recruitment (aka Self-Selection)

With the design in place, I took on the responsibility of figuring out how do we go from what we have, to what we want? I took the goal of restructuring as an opportunity to reboot the culture of the organization, to resolve as many of the issues which I found during my first 90-days. One thing I wanted to change, was to empower teams and individuals to be able to make their own decisions, to remove decision bottlenecks and allow a sense of ownership over their work and careers at SEEK Asia. I was strongly influenced by Daniel Pink’s work on motivation through the pursuit of mastery, autonomy, and purpose (4). I came up with a program to both reorganize people in to teams and domains AND empower the individual: with the concept of mission recruitment and the mantra recruit, not assign.

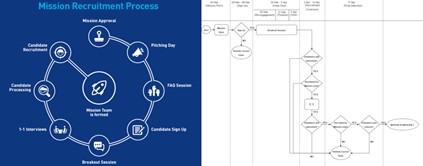

Each team is built according to the team blueprint, led by a Product Owner. Initially, we recruited the Product Owners to select available *missions. We recruited Product Owners from the pool of Product Owners and Delivery Managers. We mapped each mission to a specific customer domain and a portion of the customer journey. Once each Product Owner had their mission, they had then to recruit their team members from the pool of engineers and supporting roles. To allow for self-organization, I wanted to set rules as constraints for self-organization. We established a set of constraints or rules to govern mission recruitment:

- Each team had to have a clear mission and KPIs.

- Everyone had to sign up for a team. If you choose not to, express your concerns to a senior leader.

- Team membership had to fit within the definition of the team blueprint.

Before mission recruitment day, I had sensed that the middle managers were excited, skeptical, or a mix thereof with what we were aspiring to do. I had to work with each manager individually to hear their concerns and to partner with them to address their worries. I wanted them to feel that there was a part of this, rather than for this to happen to them.

This was one of my better decisions and many saw the reasons for what we were doing and became supportive of the change. What I had also observed was that as more managers became supportive, the ones who were skeptical became less so. While there were a few managers who were still resistant, we could not wait and had to start something.

As we had never done this before and I was not sure if it would even work, we minimized the risk by reorganizing by location. With my team of Agile Delivery Leads, we designed a mission launch day. It was a half-day event, where leadership would communicate the why of what we were doing, address questions and concerns, and introduce the mechanics of the day’s events. Product owners did their pitch, people could ask questions, have hallway conversations, or whatever they had wanted to do. I intentionally gave them space.

Once the pitches were over, sign-ups began where people could express their interest in which teams they were interested in joining. This kicked off two-and-a-half weeks where the Product Owner could then interview each candidate. This was not a traditional interview whereby a Product Owner could pick who they wanted; team members could also pick which team they had wanted to be on. We wanted to ensure that there was a suitable match on both ends, to ensure that no one felt we forced them to join a particular team or to accept a particular team member.

Figure 3. Mission Recruitment Process & Flow

At the start of implementing this reboot, I was anxious and had several concerns:

- What if no one wanted to join a team, either because of uninteresting work (legacy support) or not liking the Product Owner?

- What if an individual chooses not to sign up?

- What if an individual was not recruited or accepted into any teams?

Nevertheless, we launched our first round of mission recruitment at our first location in March 2019, recruiting for four teams from a pool of 30+ engineers, designers, and agile delivery leads.

This happened: everyone signed up, some managers signed up to be engineers, and one person was not recruited to be on a team.

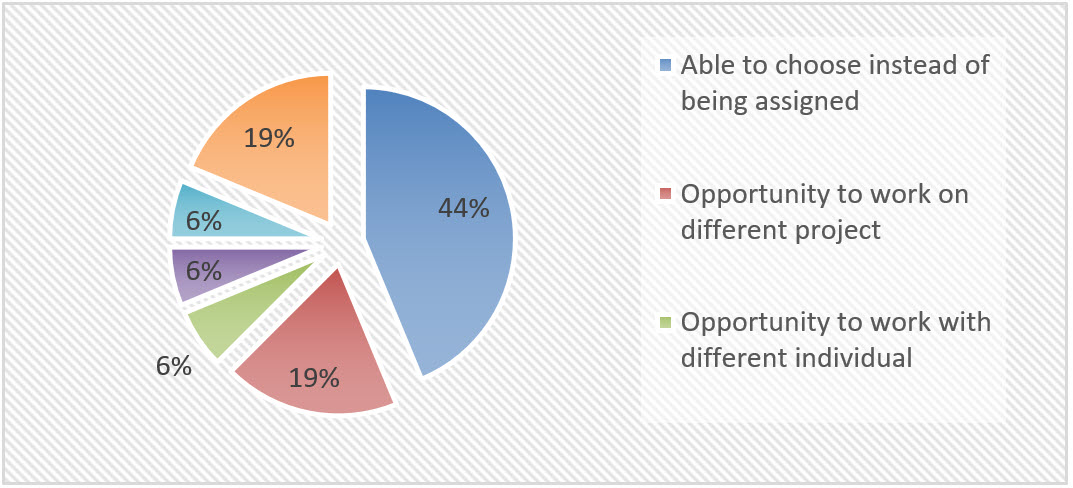

One of my goals was to allow people to make their own decisions on choosing which team they wanted to join. What was interesting was why people choose which teams to work in. For some, it was to work on a specific part of the customer journey. For others, it was to avoid a specific product owner or to work with specific team members.

It was remarkable how well it worked out, once team members were convinced that they could make their own decisions on where they wanted to be and who they wanted to work with. A pulse check on employee engagement showed that a large majority of the team members in this location felt positive, and team members in other locations were looking forward to their opportunity to be recruited.

For the sole person who was not signed up at the end of the day, I worked with that individual to design a role that was suitable for them, with consultation from the CIO and CPO; whose responsibilities were to support our transformation. That individual eventually became one of our highest performers.

We had large amounts of resulting issues, even though they were planned and catered for. Issues were mainly around the transition of responsibilities, knowledge exchanges, and production support. As a leadership team, we expected these to occur and dealt with them as they occurred.

What I feared did not come to pass, and we ran mission recruitment three more times in the remaining locations, each time improving on the process. We ran one round per quarter and each subsequent round was both smoother and more successful.

The transformation had become, though, what came next both exciting, harrowing, and long. I have heard that transformations were more marathons than sprints and I experienced it for myself.

Figure 4. Post Recruitment Survey Result

3.2.3 Establish Mechanisms for Constant Feedback

With the amount of change, we felt we were flying blind. We were moving the control levers but were not receiving any feedback. It was difficult to tell what was working and what was not. I was especially focused on how the changes were affecting our employees. What we had at the time were yearly employee engagement surveys. This was not good enough for me. I felt like I was taking a hot shower, adjusting the knobs and only feeling the change hours later. I wanted finer controls and feedback.

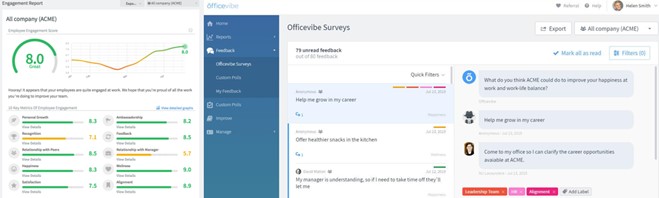

With a peer, we proposed and eventually subscribed to OfficeVibe, a real-time employee engagement service. Through continuous employee surveys, we could measure employee engagement more frequently and highlight areas that were healthy and areas that required more attention and concern.

Figure 5. OfficeVibe’s Employee Engagement Dashboard & Employee Feedback Survey (Representative)

Particularly helpful was OfficeVibe’s ability for employees to provide anonymous feedback. We wanted our people a safe avenue to express their concerns without fear of retribution. Through OfficeVibe they could provide anonymous feedback and allow us to be aware of and to resolve these concerns, rather than to let these issues persist and fester. While this created an additional management burden, it allowed us to progress towards sustain our transformation.

With my team, I had also introduced numerous channels to engage with our people to promote transparency, visibility and get feedback: monthly town halls and product showcases, leadership ask-me-anythings (AMAs), public iteration reviews, public Objective Key Result (OKR) feedback sessions, skip level 1-to-1s, and transparent dashboards. My role and my team’s role were to introduce and sustain these practices until they became an organizational habit.

3.2.4 Valley of Despair

The next 12 months were especially difficult. With each location’s reorganization/mission recruitment, there would a myriad of resulting issues. These included platform support (which team handles what?), staffing issues (turnover, new joiners, complaints), and leadership coordination.

There were plenty of resulting issues that had to be addressed. I felt as though we were driving a bus that was increasingly speeding down a highway while upgrading the road at the same time. There were large issues, e.g. finding a home / responsible team for a product service or component that fell through the cracks, and there were small issues, e.g. rolling new laptops out to teams to replace aging hardware and desktops and having teams and individuals complain about why other teams got it before they did!

Some issues resulted from change and restructuring, although some issues resulted from leadership miscommunication and alignment. It was difficult to keep track of everything that was going on and sustain a certain level of performance and behavior that is expected as a leader in this organization. I had to eventually learn how to ask for and give support to my peers, to discuss both work and personal issues, to have and be a sounding board.

This experience taught me the importance of developing the capacity to be persistent, resilient, and empathetic as a leader. To give and receive support and accept the issues that occur and working with others to resolve them.

3.2.5 I Became My Org’s Scrum Master

I eventually approached my role as my organization’s Scrum Master. I was the impediment identifier/remover of last resort. A personal performance metric of mine was how many issues could I resolve at my level and not have it escalated to the executives?

I would solve as many problems as I could, be it large or small. This was quite difficult to sustain, although it gave me a very broad view of what was happening within the organization. This allowed me to more be more empathetic of the issues faced by the teams. One issue that was clear what that there was too much change. I called this change fatigue.

To remedy this problem, I proposed for our leadership team to use a change backlog and implement a change-in-progress limit. The board and backlog would make it clear to the leadership team which changes were taking place and which remained open. Before we could embark on another change initiative, we either had to complete or end an initiative. This level of discipline enabled us to be more focused and aware of how we were affecting our teams. The CIO had also placed another constraint – any change had to have two senior leaders involved, as a form of pairing. This promoted alignment and collaboration within the leadership team.

Another item that we had implemented was Management Service Level Agreements (SLAs). These SLAs were around how quickly we had to respond to employee feedback, complaints, and issues. We intended to keep existing issues at a reasonable level and do not leave things open and unresolved. Much like how our customers dislike having open and unsolved support cases, our team members dislike open and unaddressed complaints.

Last, I instituted regular retrospectives on how we were doing as a leadership team. This would be a combination of leadership retrospectives and data gathered through employee engagement surveys. At regular intervals, we would identify issues, create a shortlist to address and communicate them openly through our town-halls. We would track these issues and provide regular updates.

4 Results

At the end of 2020, we had attained the following results:

- Deployments to production were 1000+ deployments per month. We eventually stopped counting, as it was no longer the bottleneck in serving our customers.

- ~95% of support issues met the Service Level Agreement.

- Staff turnover reduced by 50%, within industry norms.

- Employee engagement over 70%.

Business-wise we remained competitive, though significant challenges remain. What we had now is a common platform, a single organization, and an organizational culture to take on these challenges. As a bonus, we were awarded with the Agile Great Place to Work (5) award by the World Agility Forum 2020!

Figure 6. World Agility Forum 2020 Agile Great Place to Work Award

5 What I Learned

Looking back at my time at SEEK Asia, it was truly amazing how our transformation turned out. While I was in the middle of it, I found it was challenging, difficult, and, at many times, depressing; before leaving the organization I had interpersonal retrospectives, that is on a 1-to-1 basis, with my peers, a few executives, team members, and members of my team. I’ve since integrated and synthesized the key lessons that others experienced, as well as from my own journey.

5.1 The Organization is the Product

I was very outcome focused. Even though there is a myriad of agile methods, processes, and tools, they were always in the service of the outcome. I approached transforming the organization how I would approach developing a product – by focusing on customer outcomes, understanding the problem domain, prototyping, experimenting, and finally scaling.

I did not approach the problem with the view that I had a solution, but rather, that I first had to understand the problem followed by ideation and experimentation. My thinking was informed by various sources, Design Thinking, Lean Startup, Kent Beck’s 3X (6), and my experience in developing successful products. Not everything that we tried was a success. I would attribute my success rate to around 50%. What I did was to stop initiatives that were not yielding the expected results and either kill or tweak them and re-run them. For those that were successful, I would work with the leadership team to scale them quickly. In the latter half of our transformation, we had engaged with our staff in running ways of work experiments.

For example, we introduced techniques in how we would identify our quarterly OKRs. A few of us were strongly supportive of the Results Map technique from the PuMP framework (7) to create robust Key Results. We would articulate the problem clearly, enroll a couple of Product Owners to run an experiment for a quarter, and assess if it were more effective or not. The moment we had evidence that this method was superior to our existing methods and old processes, we would design a program to “roll it out” to a wider audience. Introducing change this way was more effective and less disruptive overall.

I strongly believe that approaching transformation with this mindset was critical to our overall success. It allowed us to pivot quickly, respond to our employees and changing circumstances, and engage our employees in a lasting and meaningful way; that they were part of the change rather than to have change happen to them (8).

5.2 Let the Agile Values and Principles Guide the Transformation!

Having come into this role without a background or experience in change and transformation, I leaned on the founding values and principles as an agile practitioner: focus on value, not activities; and establish principles, not directives.

This required a lot more work to align my fellow leadership peers and more than a few of our staff would simply ask us to “just tell us what to do,” though focusing on values and principles eventually created for us a culture where individuals and teams could be self-organized, teams could be highly aligned, and allowed more of the organization to take part in our change and transformation.

I found the Manifesto for Agile Software Development to be a remarkable document, where I would return from time to time for inspiration and find something new in it. In times where I felt lost, I would find guidance in other change management-related material, though I would come back to the Agile Manifesto consistently to remind myself why we’re doing this transformation.

5.3 Constantly Inspect and Adapt

A key tenet of Scrum and many agile methods is the empirical method; that is whatever action we take has to be based on a set of hypotheses and its success or failure to be based on measurable evidence.

By identifying what I don’t know, I could identify my assumptions and hypotheses. By looking at the evidence, I could look at when I had to stop, tweak or scale. It allowed me to make more rational decisions and not be attached to a particular idea or initiative. By being open and flexible it has allowed me to better collaborate with my leadership team members and be open to suggestions and ideas from the rest of the organization. Through living and behaving in this way, I and others of the leadership team could be role models for others to experiment, and create a safe to fail environment. Ultimately, change is constant, and we have to constantly inspect and adapt to survive, grow and thrive.

5.4 If I had To Do It Again

If I had to do this all over again, I would keep most of it the same, though I would have done a few things differently:

5.4.1 Create a Leadership Support Group Early On

Having gone through management school, one thing that they don’t teach is the emotional and psychological capacity required to undergo long periods of ambiguity, change, and challenges.

Throughout my time at SEEK Asia, a large part of it was under conditions where we could burn out – long hours, never-ending issues to solve, and conflicts. This had bled into my personal and family life. My fellow leadership peers had also undergone similar challenges. Only towards the end of my time there did we talk more in depth about our emotional and psychological needs and how to meet them, to allow for us to work at a healthier, sustainable pace.

By being able to address these issues, it would lead to better work relationships which would then directly affect our collective success, as the decisions we make and how we behave affect our people and organization.

5.4.2 Be a Better Storyteller

For most of our transformation, we had approached it intellectually, by communicating on the state of our organization, its impending threats, and reaffirming our aspiration. I would describe it as very head-level.

To engage a person fully, we have to make sense of the head and pull at the heart. An organization’s culture comprises the stories and narratives that exist within it and we should have formed new narratives earlier on. This was crucial given that this organization was both founder led for most of its existence and many of the older employees were constantly referring to past stories. By not affecting the existing narratives, we could not directly affect lasting change.

If I had to do it again, I will be a leader as a storyteller. I would more quickly craft new narratives to inspire to attain new aspirations. To influence the head and tug at the heart, to make it a whole-being transformation.

6 Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following individuals where without you, we could not have achieved what we did. My team: Gaik Teng, Hooi Cheng, Ivan, Hui Lin, Tammie, Rai, Ikhwan, Alice, Bonnie, Kavitha, Andreea and Connie. My peers: George, Daniel, Baraa, Mohsin, Jeremy, Naresh, Homaxi, Raoul, Jane, Maarten, Jerome, and Roger. The people who kept me sane and were my sounding board: Eric, Karen, Varun, Salman, Salam, Anne, Ali, Evan, Amen, and Maz. Last, two amazing product-led, people-oriented executives—Daniel and Ken—without whom none of this would likely have been a success.

7 References

- Watkins, Michael D. The First 90 Days, Updated and Expanded: Proven Strategies for Getting Up to Speed Faster and Smarter. s.l. : Harvard Business Review Press, 2003.

- Keller, Scott and Meaney, Mary. Reorganizing to capture maximum value quickly. McKinsey & Company. [Online] 02 20, 2018. [Cited: 07 01, 2021.] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/reorganizing-to-capture-maximum-value-quickly.

- Wikipedia. Conway’s Law. Wikipedia. [Online] [Cited: 07 01, 2021.] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conway%27s_law.

- Pink, Daniel H. Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. s.l. : Canongate Books, 2010.

- World Agility Forum. Winner for “Agile Great Place to Work” Award. World Agility Forum. [Online] [Cited: 07 01, 2020.] https://www.linkedin.com/posts/world-agility-forum_waforum20-xa2020-ahfactors2020-activity-6715717178861092864-DUHt.

- Beck, Kent. Fast/Slow in 3X: Explore/Expand/Extract. Medium. [Online] [Cited: 07 01, 2021.] https://medium.com/@kentbeck_7670/fast-slow-in-3x-explore-expand-extract-6d4c94a7539.

- Barr, Stacey. The Anatomy of the PuMP Results Map. Stacey Barr. [Online] [Cited: 07 01, 2021.] https://www.staceybarr.com/measure-up/the-anatomy-of-the-pump-results-map/.

- Tang, Tze Chin. CxO: You are Your Organisation’s Product Manager. Business Agility Institute. [Online] 11 28, 2018. [Cited: 07 01, 2021.] https://businessagility.institute/learn/cxo-you-are-your-organisations-product-manager/412.