Virtual Reality: Catalyzing the Future of Work

Often associated with gaming, virtual reality has the potential to drive the future of a wide range of industries. This article outlines how virtual reality will change the face of healthcare, manufacturing, and journalism.

Often associated with gaming, virtual reality has the potential to drive the future of a wide range of industries. This article outlines how virtual reality will change the face of healthcare, manufacturing, and journalism.

Toptal Research

In-depth analysis and industry-leading thought leadership from a panel of Toptal researchers and subject matter experts.

For many, virtual reality (VR) likely conjures images of game-obsessed teenagers wearing goggles, marveling at the sensation of riding a rollercoaster or floating through space from the comfort of home. But the most significant future virtual reality applications will likely go beyond pure entertainment, dramatically changing the way people think about their work.

It’s no secret that virtual reality has the potential to influence daily life. Consumer applications, such as gaming, continue to crowd headlines as companies vie to capture the public imagination and spark VR’s mainstream adoption. Since its $2 billion acquisition of Oculus VR in 2014, Facebook has been a particularly prominent player in the space, with some projecting that the company may spend more than $5 billion annually on virtual reality in the next few years. “Social is not only important to Facebook’s mission, but to the future of VR,” writes Gene Munster, Managing Partner of Loup Ventures. “VR will need a social aspect before there will be mass adoption of the technology.”

There are numerous virtual reality applications that have the potential to fundamentally shape a range of industries from manufacturing to journalism, healthcare and more.

Yet this emphasis on consumer-oriented, social virtual reality applications masks the potential VR technology has to make a splash in the enterprise space and steer the future of work more generally. There are numerous virtual reality applications that could fundamentally shape a range of industries, from healthcare to manufacturing, journalism, and more.

To understand what the future of virtual reality might look like, it’s instructive to first examine virtual reality’s past. Beginning with an overview of the history of virtual reality technology, this article outlines some of the most powerful virtual reality applications on the horizon – those poised to shape or upend entire industries. Connecting virtual reality’s history, and some of its original use-cases, with its current and future enterprise applications will clarify that VR’s technological potential has always extended far beyond gaming.

In a sense, enterprise applications actually mark a return to – not a departure from – virtual reality’s technological roots.

From the Pilot-Maker to the Sword of Damocles: A Brief History of Virtual Reality

The history of virtual reality begins decades before the term “virtual reality” was coined, and long before the rise of digital technology.

In 1929, Edwin Link built the Pilot-Maker (pictured below – also known as the Link Trainer), the first-ever flight simulator and arguably the first example of an artificial environment simulated by technology. Spurned by flight schools, Link first sold his invention to amusement parks. Eventually, however, Link’s flight simulator caught the attention of the Army Air Corps (precursor to the U.S. Air Force), which purchased six simulators in 1934. Within a few years, the Pilot-Maker had spread to 35 countries, and Link’s newest model would train 500,000 pilots during World War II.

Following World War II, virtual reality applications expanded into the entertainment industry. In 1955, Morton Heilig wrote an essay, “The Cinema of the Future,” in which he envisioned an immersive cinematic experience that stimulated all five senses (sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell). He put his idea into practice, and in 1962 patented the Sensorama Simulator, a device that incorporated sensory experiences like wind and odors at appropriate points during a given film. The Sensorama never garnered enough financial backing for mainstream adoption, but it laid the groundwork for subsequent virtual reality iterations.

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter.”

Ivan Sutherland took virtual reality another step forward in 1965. As head of the Information Processing Techniques Office at the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) – the Department of Defense’s primary research and development arm – Sutherland wrote a paper, titled “The Ultimate Display,” advancing a new model for physical interaction with the digital world.

“The ultimate display would, of course, be a room within which the computer can control the existence of matter,” Sutherland wrote. “A chair displayed in such a room would be good enough to sit in. Handcuffs displayed in such a room would be confining, and a bullet displayed in such a room would be fatal.”

Three years later, Sutherland developed the Sword of Damocles – the first virtual reality head-mounted display (pictured below).

Much like computers of the same era, the Sword of Damocles was large, unwieldy, and not suited for popular use. As the first head-mounted display, however, it established a crucial model for future, goggle-based ways of accessing virtual reality.

Why Does the History of Virtual Reality Matter?

While an early or mid-20th century flight simulator may seem a far cry from what we now think of as virtual reality, the development of flight simulator technology was crucial to future virtual reality applications. Several engineers who would later be among the pioneers of modern virtual reality, including Morton Heilig and Ivan Sutherland, were in the Army, Army Air Corps, or broader military industrial complex and would surely have been aware of – and perhaps directly exposed to – the flight simulator. Heilig, Sutherland, and other VR pioneers developed their technologies and applications in this context.

Link created the flight simulator with a practical goal in mind. Though bought by amusement parks before the military, this early application of virtual reality technology was fundamentally geared toward enabling practitioners to perform their jobs more effectively. More specifically, the flight simulator aimed to significantly influence the future of work for pilots.

Modern virtual reality applications are developed for enterprise with a similar intent and spirit in mind.

Virtual Reality Sparks Enterprise Innovation

Current and future virtual reality applications have the potential to spark dramatic improvements in a broad range of industries and revolutionize the way practitioners work within and think about their fields.

Healthcare

From the standpoint of both potential social and financial impact, physical therapy and pain management represent two of the most significant virtual reality applications currently in use. Substantial research going back to the beginning of the century has shown virtual reality to be effective in pain mitigation, and this solution has assumed a new urgency with the U.S.’s rising opioid epidemic. A 2016 study examining virtual reality’s effect on chronic pain had participants use an application called Cool!, developed by DeepStream VR in 2014 (video below). The study found that the application reduced pain by 60 percent, and that 100 percent of the study’s 30 participants “reported a decrease in pain… between pre-session pain and during-session pain.”

“We could be on the verge of a new era of pain treatment in which medications are rarely used, and VR is a primary treatment modality.”

The author of the study, Dr. Ted Jones, a Clinical Pain Psychologist at the Behavioral Medicine Institute, believes that virtual reality may one day be a viable alternative to opioids for pain treatment.

“Past studies have shown that VR is very good at pain relief, so we need to adapt what has been done to date and develop new ways of treating pain in our opioid[-taking] pain population,” Jones said in a 2017 article published in Clinical Pain Advisor. “We could be on the verge of a new era of pain treatment in which medications are rarely used, and VR is a primary treatment modality.”

As Dr. Jones’ statement implies, virtual reality has the potential to fundamentally change the way doctors and other medical professionals think about treating pain, which could also have important ramifications for a range of other players in the medical field – the drug industry and the pharmaceutical companies currently producing billions of dollars worth of painkillers foremost among them. This application also demonstrates the power of gamification – using games or game-like applications, such as Cool!, toward productive engagement with a given service.

Manufacturing

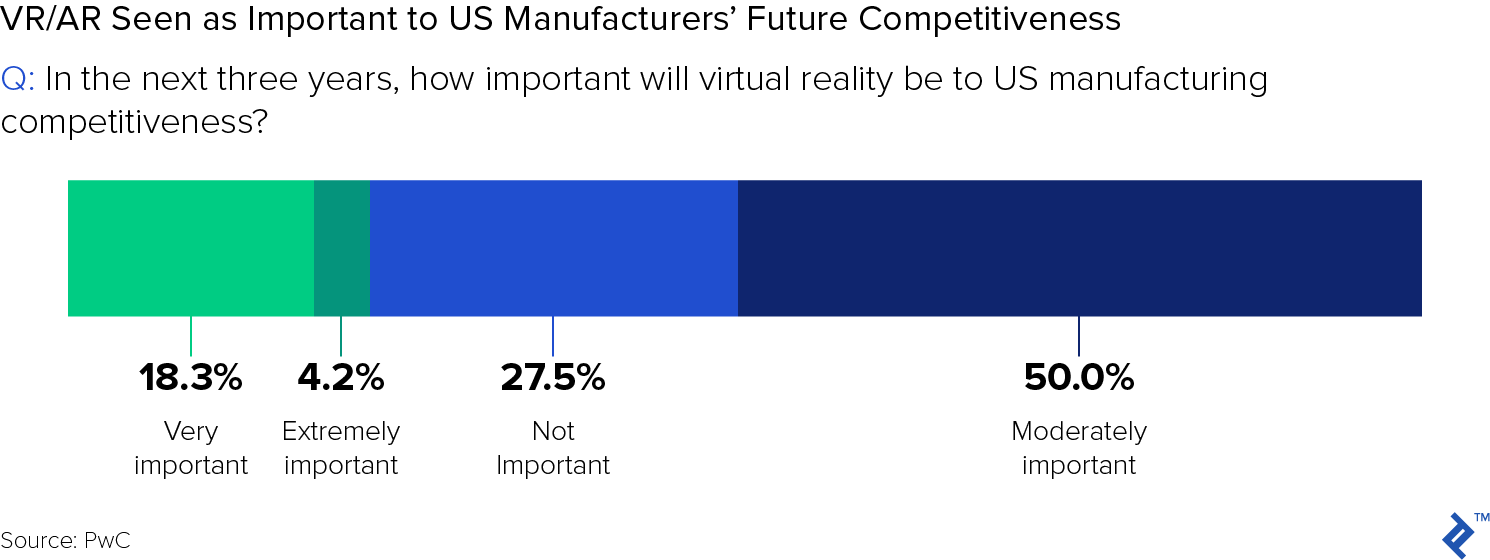

Virtual reality is also poised to influence the future of manufacturing. A 2015 survey conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) found that 72.5 percent of U.S. manufacturers saw virtual reality or augmented reality as either moderately, very, or extremely important for U.S. manufacturing global competitiveness in the next three years.

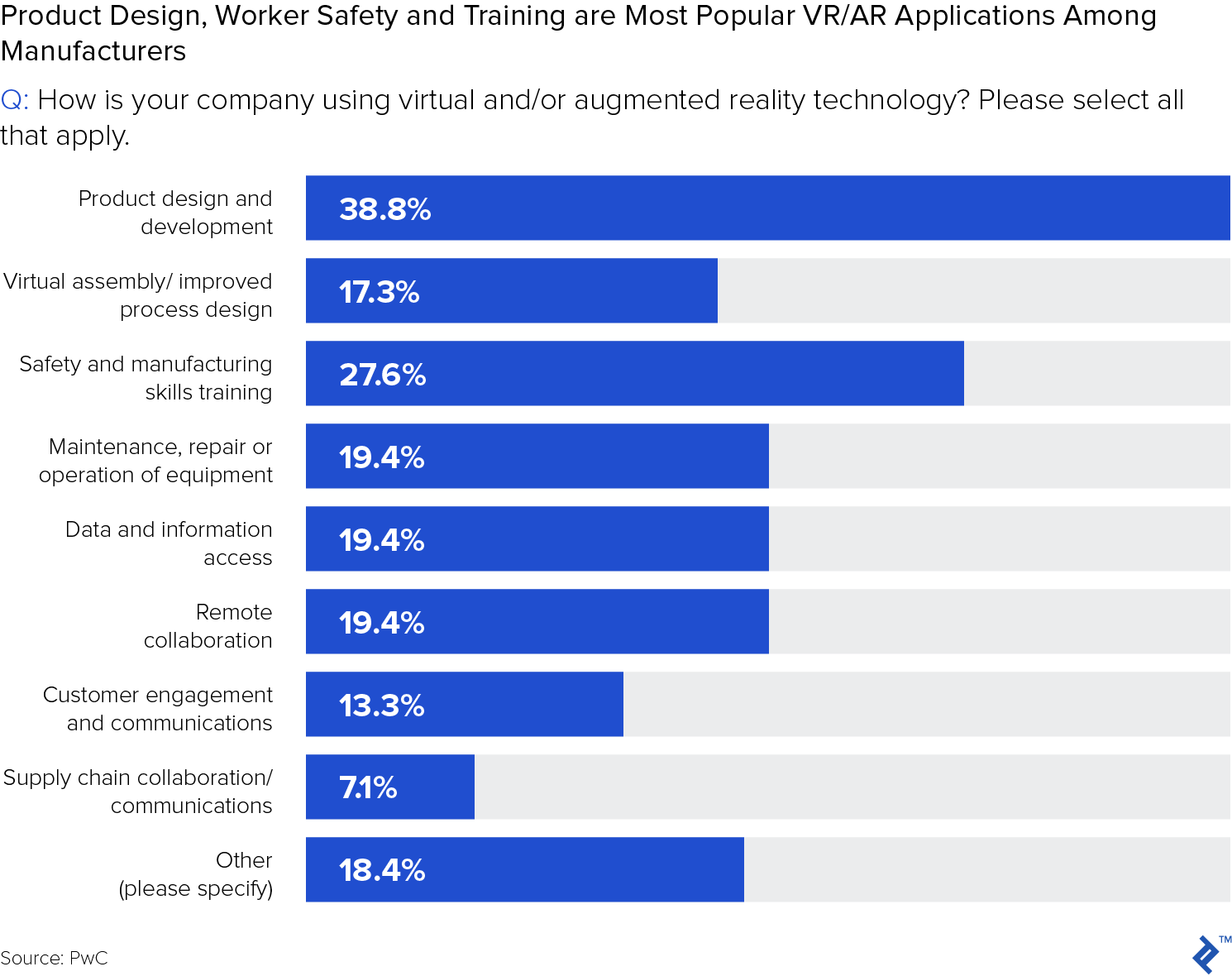

In terms of how manufacturers are actually using this technology, PwC explains further:

“[Some companies] are using [VR and AR] for remote maintenance: picture a field technician that relays a live image of a part that needs to be fixed and a remote colleague supplies relevant data, instructions or images that could serve as a virtual repair manual. Or, smartglasses that help track complicated assembly processes to ensure that all parts are assembled in the right sequence without the down-time of consulting a clipboard, manual or even tablet.”

At Lockheed Martin’s Collaborative Human Immersive Laboratory (CHIL), engineers and product designers use virtual reality to collaborate on building virtual prototypes. As Lockheed explains, “This allows engineers and technicians to validate, test and understand products and processes early in program development, when the cost, risk and time associated with making modifications are low.”

“VR enables Lockheed Martin to stretch the limits of what is possible, and at the moment, the possibilities for VR seem limitless.”

Virtual reality has changed a variety of jobs at Lockheed: “Technicians can practice how to assemble and install components, the shop floor can validate tooling and work platform designs, and engineers can visualize performance characteristics like thermal, stress and aerodynamics, just like they are looking at the real thing.”

In addition to these applications promoting greater cost and time efficiency, Lockheed sees virtual reality as a key tool for continuing to innovate: “Lockheed Martin sees many applications for VR beyond its current use. VR enables Lockheed Martin to stretch the limits of what is possible, and at the moment, the possibilities for VR seem limitless.”

While much has been written about the potential for machines to displace humans in manufacturing, virtual reality stands as a tool that can significantly enhance manufacturing efficiency without necessarily displacing human labor.

Journalism

In a sense, virtual reality represents a new mode of storytelling. It is unsurprising, then, that it is also poised to play an increasingly significant role in the future of journalism.

“Immersive content will change how journalists tell stories, and how people consume news.”

In a 2017 study, the Associated Press determined that “the production of 3D content will soon become commonplace in newsrooms around the world,” and that “Immersive content will change how journalists tell stories, and how people consume news.”

Widely-read journalistic outlets are already experimenting with such content. A 2017 New York Times piece, “Life on Mars,” included a series of 360 degree videos enabling readers to explore the “Mars-like conditions” in which a team of researchers lived (isolated on Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii) during a NASA-funded study. The Guardian has published a number of pieces employing virtual reality and has created a “Guardian VR app,” which readers can use to readily access virtual reality journalistic content.

As the aforementioned Associated Press study mentions, virtual reality has a number of important journalistic implications that require further thought, from changing what sorts of topics and content readers are interested in, to reducing the editorial control publications ultimately have. Still, it seems clear that virtual reality will play a role as journalists forge into the future.

Looking Toward the Future

With technological roots in the early 20th century, the concept of virtual reality is not new. Yet virtual reality applications are still in their infancy. We have only scratched the surface of what virtual reality is potentially capable of, and its most significant applications have likely not yet been developed.

Touched on only briefly in this article, augmented reality also stands to make a significant impact on the future of work. Rather than creating an immersive experience the way virtual reality applications do, augmented reality seeks to enhance physical objects with digital features or data. While some have suggested a sort of technological competition between AR and VR, implying only one will emerge dominant, it seems likely that both will play roles in guiding both the future of enterprise and entertainment.

Historically, virtual reality has always married entertainment with practical use. It’s clear that today’s virtual reality applications – and likely those going forward – will continue this trend. The gaming industry will undoubtedly benefit from the rise of VR, but it should come as little surprise to see virtual reality playing an ever-increasing role in the way businesses – and industries – work.