Vail Mountain kicked off the new year by setting a record. For the first week of January, a single-day lift ticket purchased on-site cost $299, the highest amount ever charged to ski the iconic resort, roughly 100 miles outside Denver.

The price was $100 higher than a single-day lift ticket just six years ago, but anyone following the industry wouldn’t have felt sticker shock. According to Vail Daily, two other Colorado resorts, Steamboat Springs and Beaver Creek, featured $299 lift tickets over New Year’s weekend. In Utah, Park City Mountain also priced its peak season one-day tickets at $299.

The exorbitant prices came in less-than-ideal weather: Vail didn’t get a single inch of snow over New Year’s weekend. Snowfall was scarce in much of the country in late 2023.

It was yet another contradictory situation for an industry that’s chock-full of them.

- Despite the rising cost of single-day tickets, American ski resorts saw 65.4m skier-snowboarder visits in 2022-23, the highest number ever. Popularity has soared because of season passes popularized by Vail Resorts and Alterra Mountain Company, which own dozens of resorts and gobble up billions in ski-related revenues.

- Although demand has soared to record heights, there are fewer ski resorts than there were 40 years ago and almost no opportunities to build new ones. That has led to overcrowding at resorts operated by Vail and Alterra — but has boosted independent ski areas, which have also broken records for skiers and revenues.

How did the ski industry get popular enough to be good for both corporate giants and independents? And can they make enough snow to keep it going?

A slope-side arms race

On Dec. 14, 1980, the chairman for Vail Resorts and a group of luminaries that included former President Gerald Ford gathered at the foot of a mountain outside Vail for a day of luxury: a ribbon-cutting ceremony, roast beef and ham dinner, and cocktail reception. One attendee told the local Daily Sentinel he could “almost see dollar signs carved in the trees.”

It was opening day for Beaver Creek Resort, one of the most-hyped ski areas in Colorado history and a symbol of the sport’s turn toward luxury and growth.

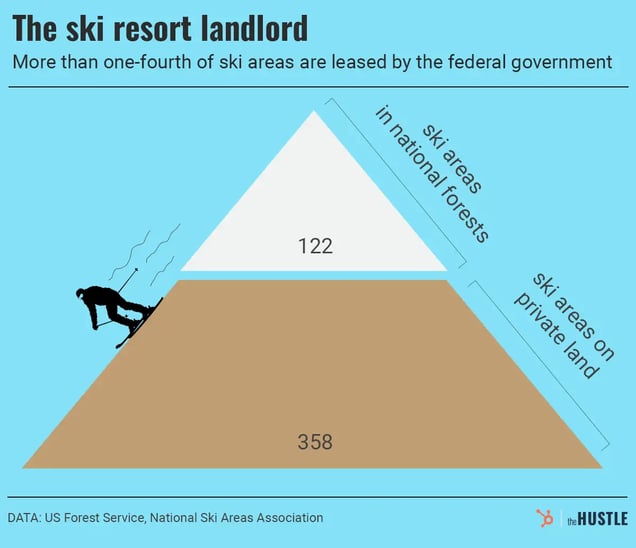

A few decades earlier, the US Forest Service jumpstarted the industry by carving modest ski trails into federal forest lands. The organization began leasing permits for the areas to private groups, leading to the development of famed resorts like Alta Ski Area in Utah, Taos Ski Valley in New Mexico, and Keystone, Vail, and Breckenridge in Colorado.

The Hustle

The operators of the resorts paid pennies on the dollar for the permits. By the 1970s, the US had more than 700 ski areas, with over 100 in federal forests.

But the growth ended there. Beaver Creek ended up as the last major ski resort to open in Colorado and one of the last to open in the US.

By the ’80s, nearly all the best land for ski areas — mountainsides that got enough snow and had terrain for green, blue, and black slopes — was used up.

At the same time, new environmental regulations and protests over the development of federal forest land made building resorts more litigious and expensive. Before its opening ceremony, Beaver Creek endured years of uncertainty.

- Vail Resorts originally filed for a permit with the Forest Service to develop Beaver Creek in the early 1970s to help host the 1976 Winter Olympics. But Denver residents voted to reject funding for the Olympics, forcing the International Olympic Committee to select a new host city and putting the planned resort at risk.

- An outgoing governor’s administration recommended the Forest Service approve permits for Beaver Creek in January 1975, days before a new governor who planned a moratorium on ski areas took office.

Gerald Ford hits the slopes at Beaver Creek. (Duane Howell/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

Beaver Creek wasn’t the only resort facing turmoil. Difficulties were reverberating through the industry.

“With the inability to add more resorts, that means you have to get into an arms race,” says Michael Childers, author of Colorado Powder Keg: Ski Resorts and The Environmental Movement and a professor at Colorado State University. “You have to start increasing development on the resorts that you have.”

Ski areas started to invest more in lodging, restaurants, high-speed chairlifts, and snow-making machines, the latter becoming an absolute necessity so ski areas could stay open as much as possible.

Downhill skis for sale in Vail. (Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

Given the high costs of capital improvements, Childers says, the industry started consolidating “into just a few corporate and investment firms.” Some were an odd fit for skiing:

- Moore & Munger Inc., a wax and petroleum company, bought two major resorts in Vermont.

- The movie studio 20th Century Fox purchased Aspen Skiing Company, owner of three Colorado resorts.

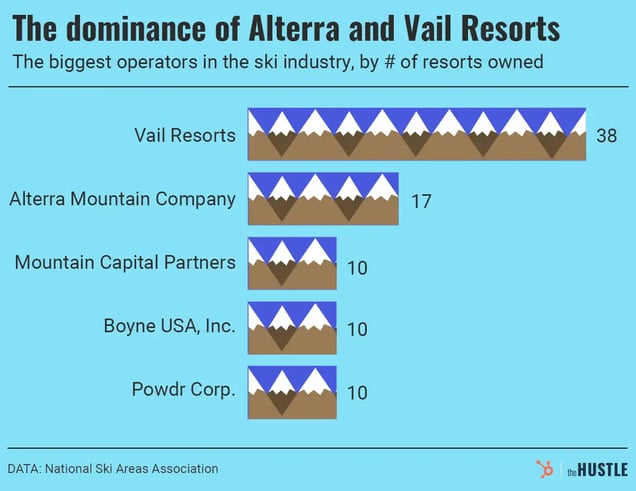

Many independent ski areas didn’t survive, merging or closing. By 2000, the number of US ski areas declined to 489 (it’s now at 480). One dominant player emerged: Vail Resorts.

Beaver Creek was just the second resort it operated, after Vail. But after going public in the late 1990s, the company went on a buying spree. Vail Resorts now operates 38 ski areas, according to the National Ski Areas Association. Its biggest competitor, Alterra Mountain Company, formed after the merger of two financial firms and the resort company Intrawest in 2017. It operates 17 resorts.

The Hustle

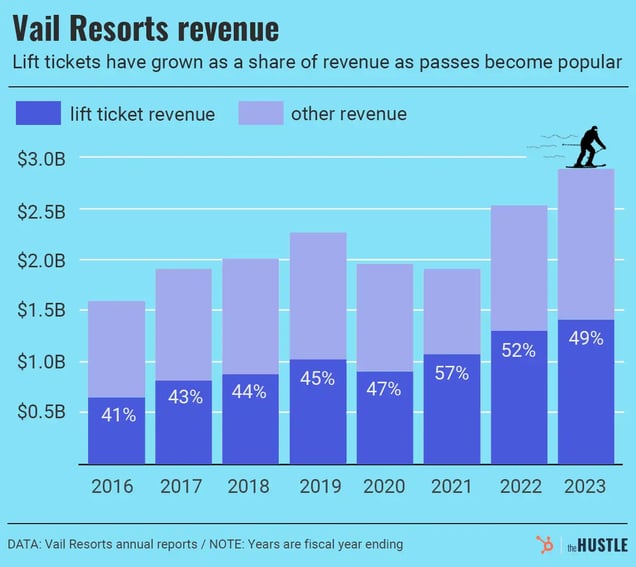

Both companies try to gain an edge by investing in high-speed lifts and gondolas to whisk skiers to the top of the slopes as quickly as possible. They also own nearly everything at the base of the mountain, from rental stores to gourmet restaurants to hotels and condos. In the 2010s, those ancillary cash streams often brought in more revenue for Vail Resorts than money from the ski lift.

But by far the most transformative change for Vail Resorts, Alterra, and the industry was season passes.

How passes changed everything

Vail Resorts first released the Epic Pass in 2008. Skiers could pay $579 and visit Vail, Breckenridge, Beaver Creek, Heavenly, and Keystone as often as they wanted for the upcoming ski season.

It wasn’t the first season pass — Colorado’s Winter Park offered a heavily discounted pass in the late 1990s, starting the trend. But this pass granted entry to five resorts, which at the time charged up to $90 for a single-day ticket.

Vail Resorts sold 59.1k passes the first year, totaling $32.5m. That number increased to 650k in 2016, 1.2m in 2019, and 2.4m in 2023 for ~$900m in sales. The cost for an Epic Pass for the 2023-24 season started at $909 last spring (rising as ski season approached) and offered buyers unlimited admission to every Vail Resorts ski area.

During an earnings call in December 2023, Vail Resorts CEO Kirsten Lynch said passes made up ~73% of the company’s overall lift-ticket revenue, giving the business more stability. The upfront money is a hedge for seasons with lower snowfall and bad weather. Plus, Vail Resorts and Alterra (which has the similar Ikon Pass) can reinvest in lift technology and snow-making and charge a premium for single-day entry.

Skiers, meanwhile, have seized on the discount and started skiing more frequently. Ski weekends in many parts of Colorado have gotten longer, says Childers, with people arriving a day earlier or staying a day longer. US skier visits for the 2022-23 season, at 65.4m, were up nearly 10% since the first year of the Epic Pass. And the sport is growing: The total number of US skiers reached 11.6m last season, up from ~10m in 2008.

The Hustle

Not everyone is happy, however. Season passes, and the growth of Alterra and Vail Resorts, have attracted their fair share of critics:

- Skiers bemoan crowded slopes caused by season-pass holders flocking to whichever ski area has the best snow in a given weekend.

- Mountain-town residents are angered by the corporate makeovers and job cuts after resort acquisitions, as well as the companies’ contributions to skyrocketing housing costs.

- Families who make a last-minute decision to ski can end up paying exorbitant prices for single-day tickets.

But there’s one group that’s been surprisingly pleased with Alterra and Vail’s business model: indie ski areas.

A new indie golden age

In 2019, Vail Resorts expanded further into the East Coast with its purchase of Peak Resorts, the owner of several ski areas in Vermont, New York, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania. They were now competing in the same territory as independent resorts like New Hampshire’s Pats Peak, Vermont’s Magic Mountain, and Massachusetts’ Berkshire East.

Except it hasn’t felt like direct competition.

“It opened up space for us, as crazy as that sounds,” says Jon Schaefer, whose family has owned Berkshire East since 1976 and who bought New York’s Catamount Ski Area in 2018.

Skiers in Vermont. (Wikimedia Commons/Getaway-Vacations.com)

In Schaefer’s view, Peak Resorts had been trying to provide a larger-scale version of what indie operators did, offering group discounts, midweek deals, and experiences that varied at each ski area. But Vail Resorts has done the opposite: streamlined operations and focused on passes and expensive day tickets. Where online single-day tickets ranged from $100 to $135 at Vail’s Mount Snow in late January, Berkshire East tickets went for $38 to $71.

Since 2018, Schaefer’s revenues have more than doubled. He attributes the gains to the increase of skiers in the US and to indie resorts “touching the right chord” as resorts operated by Alterra and Vail experience a crush of traffic and visitors.

“A lot of people just like the big mountain; they like to have a few cocktails afterwards and all the amenities and being around thousands of other folks having fun. That’s got its own energy, too,” Schaefer says. “We just seem to find more and more people that like what we’re up to, and that’s working for us.”

A snow-making machine. (Sun Changshan/VCG via Getty Images)

At Pats Peak in New Hampshire, general manager Kris Blomback says his resort is thriving, and he’s heard the same from other ski area operators. One reason is the Indy Pass, a season pass that grants entry to dozens of independent-owned resorts.

- Season passes at Pats Peak now account for ~60% of lift-ticket revenues, up from ~25% ten years ago.

- Overall, lift-ticket revenues at Pats Peak account for ~40% of revenues, with food and drink and ski school coming in at ~15%-20% each.

“We’re kind of like a little city when we’re up here operating,” Blomback says. “People come and they buy a lift ticket, but we’re also feeding them. We’re also taking care of the kids.”

And to keep operating, Pats Peak requires the same key ingredient for any ski resort: snow.

Pats Peak makes it almost constantly, to stay open for as long as possible. Although snowfall in future winters is expected to decline from climate change, Blomback says his resort still gets a steady 60-80 inches per year.

In the ’70s and ’80s, ski areas might’ve used artificial snow on 25% of their trails, Blomback says. The most competitive areas now aim for 80% coverage as early in the season as possible, relying on historic snow averages and temperatures to estimate how many gallons of water they need to pump into snow every day.

When they get that equation just right, it means an endless forecast of beautiful powder on the slopes — and profit for the resorts.