You’re going to be judged on the first thing you launch — everyone is. Explaining that it’s just your minimum viable product (MVP) and it’s not ready yet is sometimes fine, but I’ve seen many times where that’s the dealbreaker in itself.

Why? Because your idea of minimal is far more minimal than that of the person you’re showing it to. Minimal is a sliding scale that will always slide onto you.

The notion of the minimum viable product (MVP) has always had its pros and cons, but the often bitter cocktail of time pressure, competition and agile software development made the MVP the ongoing easy choice.

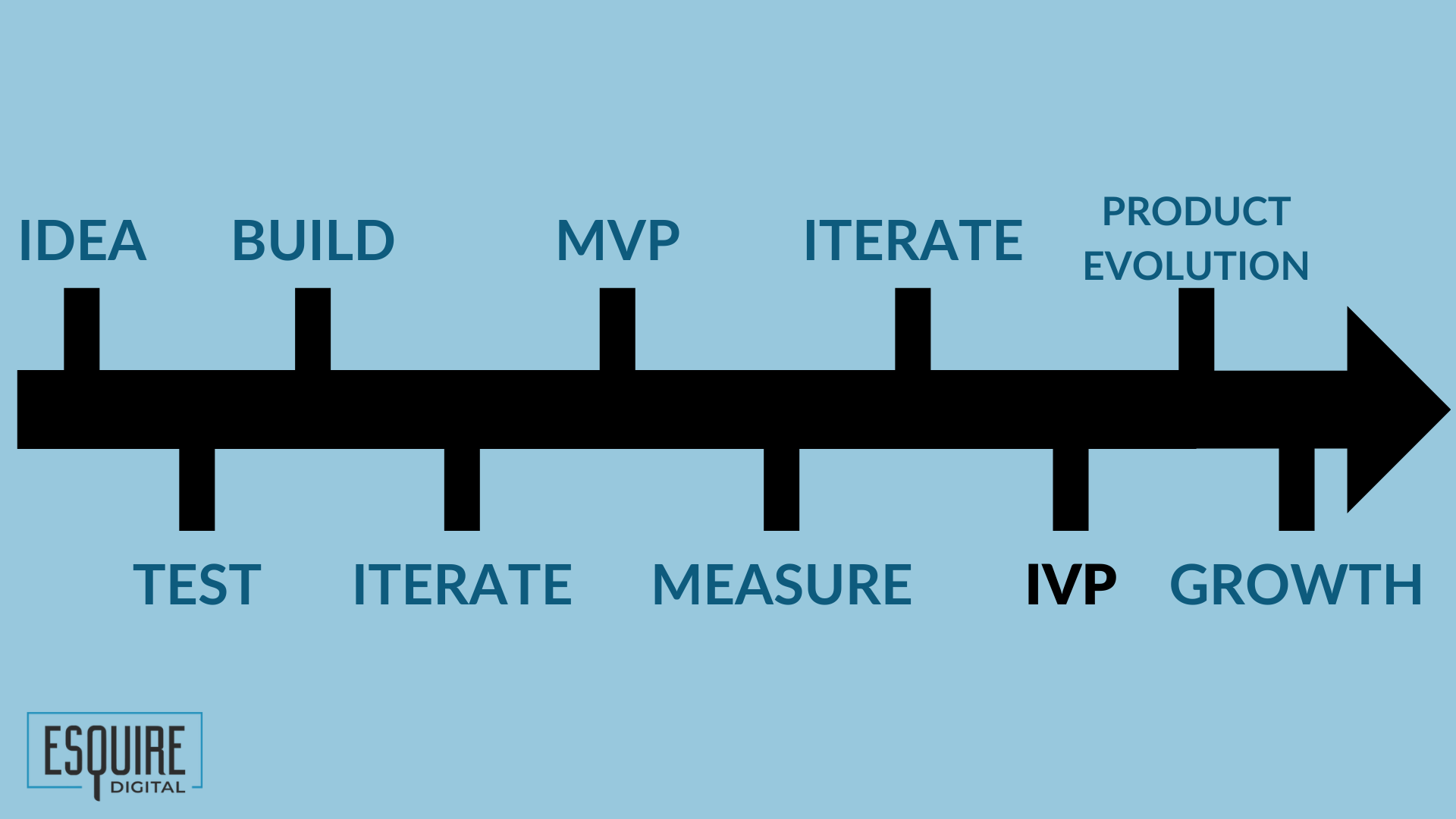

My concept of the initial viable product (IVP) isn’t just a hyperiterated MVP. It’s the first truly viable product you choose to launch. On the continuum of idea to completely finished product, the IVP is simply the release of a non-minimal product.

Image Credits: Esquire Digital

Your IVP should eliminate any conversation about whether the product you’ve released is indeed viable. If your IVP is your presentation of unbaked pepperoni pizza, your MVP is when you present a can of sauce, a package of cheese, a Slim Jim and a pencil sketch of an oven.

I remember a conversation in Beijing with an entrepreneur looking to reinvent taxis. Not the service itself — Didi and Uber were just about to be born — but the notion of the traditional Beijing taxi itself. How to make it safer, more fuel-efficient, less harmful to the planet and all around better.

Starting further along the continuum than an MVP made a lot of sense, because there really couldn’t be anything minimal about the redesign of a taxi — it’s kind of revolutionary by nature. A decade ago in Beijing, presenting something minimal might have gotten you laughed out of the room. Not having the connections and therefore the capacity (read: funding) to build a true IVP was an immediate and likely fatal show of business weakness.

Y Combinator explains why the MVP is by nature a process more than a product, and that’s fine for a philosophical discussion. But the inherent instability of the MVP is often more trouble than it’s worth. It’s true, as YC points out, that an MVP isn’t something you build once and call it a day. But as was the case with my Beijing taxi example, your initial product needs to be viable, and sometimes designing and building the minimum just doesn’t cut it.

I remember an exercise we did in a senior-level entrepreneurship class I taught at McGill University. We were working with Alex Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas and trying to figure out how minimal of a product we would need to reach viability and therefore be able to apply the canvas.

As we played with some real-world examples, the students were the ones pushing for what I define here as an IVP.

For them, the MVP was too malleable, and they wanted something with a more defined form. The MVP is great conceptually, and the students could easily wrap their individual and collective minds around it, but when they began to play with it in practice, it was often not so great.

Lawyers also love the IVP. Jeff Zenna, a New Jersey lawyer, says more developed ideas are better and safer from a legal perspective. “The further along an idea is, the better able a lawyer is to protect anything within that idea that the law sees as proprietary. This could include copyrights, patents and other intellectual property.”

The notion of delivering the first thing we can, as long as we can argue that it is minimally viable, almost ironically runs counter to the startup ethos. “Just ship it” doesn’t mean just ship the airplane as an empty metal tube with engines. It means that you should focus from day one on shipping something great, or at least good. Minimum is minimal, and it seems that when we aspire to achieve the minimum, we often fall short of even that.

The more we consider what we actually choose to release for even quasi-public consumption, the easier it is to set our intention of how we want our product to be perceived, discussed and used.