Earlier today, The Exchange dug into changing investor sentiment regarding growth and profitability. A new report looking at cloud and software companies from Battery Ventures ran the math on how investors are rewarding faster growth from less unprofitable companies — dare we say, profitable companies? — with the data indicating that, at least for now, growth is no longer enough to maximize corporate value.

For startups busy stacking new revenue with minimal burn, the situation is good news. For companies that raised while money was cheap — and sitting on huge valuations predicated on yesteryear’s valuations — the news that profitability is in vogue again is far from welcome. Many unicorns are likely now trapped between changing investor preferences and a general compression of the value of software companies.

Why? Because many a unicorn was minted during the 2020-2021 era on the back of quick revenue growth more than anything else. And, as revenue multiples stretched to the sky during that time period, a great number of startups reached the $1 billion valuation threshold — or a multiple thereof — on the back of small, if quickly expanding, top line.

If revenue multiples have come down, that’s bad news for unicorns. If revenue multiples have come down and growth is losing comparative luster to profits, high-burn unicorns that were once valued more for something else are doubly bound by changing market conditions.

Even worse, Battery points out a few difficult facts about just how many unicorns might be able to go public in the coming years compared to how many unicorns there are in the market today. There’s a lining of good news in the data for truly standout startups. But for the bog-standard unicorn, there’s more than just storm clouds on the horizon.

Why is the math bad?

In the last 10 years, Battery counts 200 software companies that went public. In contrast, the venture firm counts more than 1,000 new unicorns minted over the same time frame. That’s a 5-1 ratio of IPOs to new billion-dollar companies.

Image Credits: Battery Ventures

Why contrast the two figures? Because almost any company that generates a $1 billion private-market valuation is a company that we expect to go public. That’s what a private-market valuation in the 10-figure range means. Sure, some will get acquired, but most are going to need to go public to return investor capital.

Naturally, both figures were greatly expanded by the 2020-2021 venture capital boom. Venture money flowed freely, creating many more unicorns. And the same warm period for tech valuations saw more IPOs than we can remember in any other recent period. So, the two balance out, right?

No. They do not, because the current pace of IPOs is zero, and unicorns are still being created while the overhang of yet-private billion-dollar startups stretches to the horizon. It was always going to be tough to get even a quarter of unicorns through the IPO window, it appears, given historical data.

Returning to the burn-growth balancing act that investors are now demanding from tech companies big and small, you can see why we are somewhat pessimistic about the chance of most unicorns going public at a billion-dollar price or greater in the next year. Not only have there never been enough IPOs for that to happen, but how unicorns were once valued is now out of fashion (high-burn growth), and the value of that original substance has been curtailed (via revenue multiples compression).

Unicorns at once need to greatly improve their profitability and expand their revenues more than expected just to defend their valuations thanks to lower multiples. How do they do that — cut losses while also growing quickly enough to earn their now-dated pricing under new market conditions — before running out of capital? Maybe they do not.

That means we could have more unicorn deaths in the next few years than unicorn IPOs. Still, there is some good news for unicorns: The metrics they need to get out of their jam are somewhat understood.

How to ensure that your unicorn makes it

For your unicorn to survive, the first rule of thumb is that it should be more than a unicorn: It should also be a centaur. Coined by Bessemer Venture Partners, the term refers to cloud companies with more than $100 million in annual recurring revenue (ARR).

Battery concurs that overcoming $100 million in ARR should be part of the road map of a healthy cloud company. However, its report paints this figure as the lower end of the ARR range that could eventually reach 10 figures.

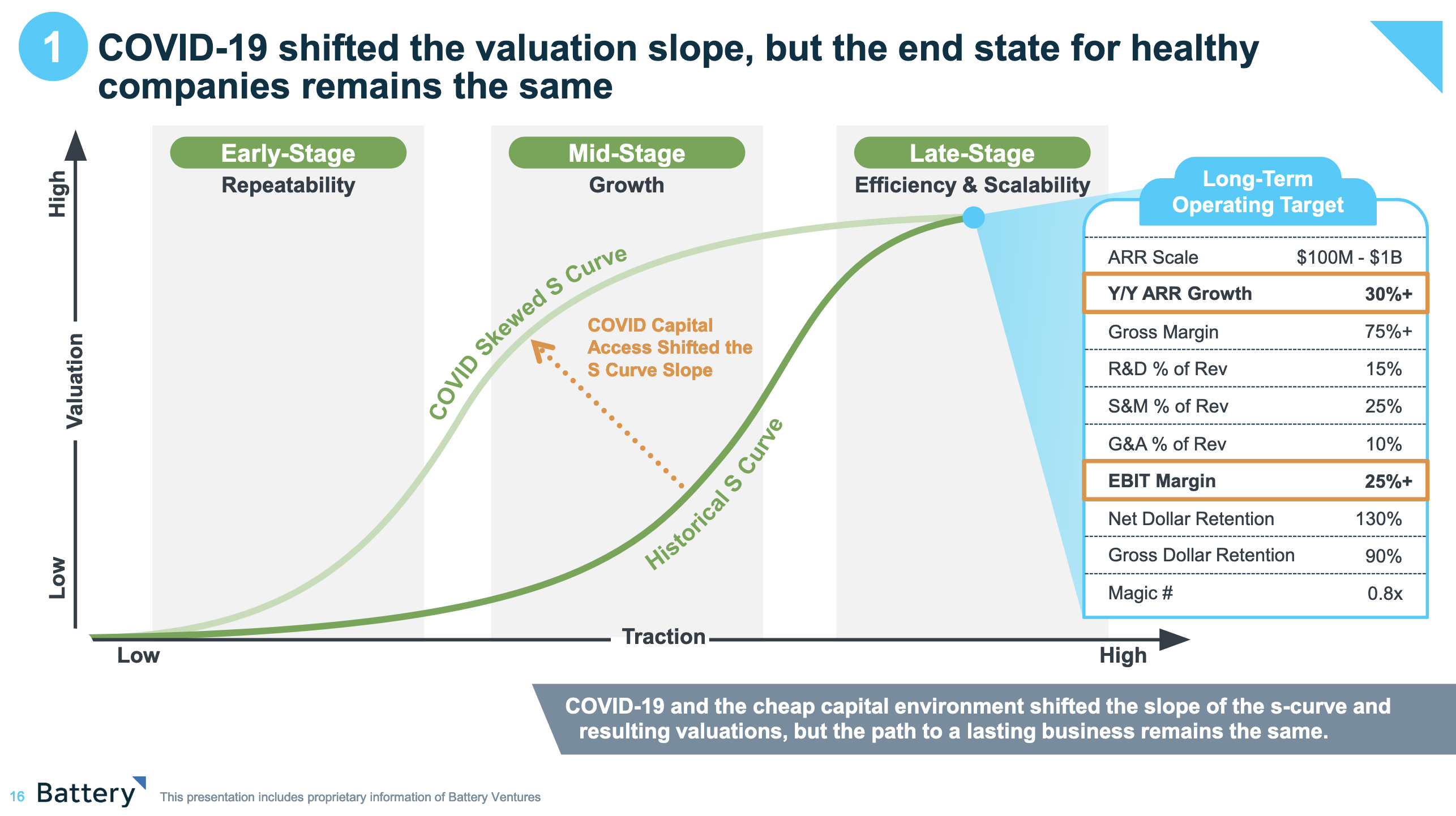

In the following chart, the venture firm sets out a “long-term operating target” with key metrics that a late-stage cloud company should aim to achieve:

Image Credits: Battery Ventures

There are quite a few acronyms on the chart, some lesser known than others, so let’s just note quickly that R&D stands for research and development; S&M, for sales and marketing; G&A, for general and administrative. As for the magic number, it balances growth in revenue against sales and marketing spend.

The magic number is considered a key tracker of efficient growth, a concept that sums well what investors want to see: growth, but not at any cost. Hence the importance not just of ARR increasing by more than 30% year on year, but also of EBIT margin being above 25%.

The fact that Battery’s chart includes targets for net dollar retention (above 130%) and gross dollar retention (90%) is also telling. It gives founders an idea of what to prioritize and improving NDR is definitely on the list.

The next question, of course, is how. We’ll explore this further shortly.