It’s not a bad year for startup fundraising. While venture totals are off sharply from records set last year, evidence is accumulating that 2022 is more of a return to an elevated baseline than a historic collapse.

According to a review of a Crunchbase dataset tracking funding for unicorn companies — private startups worth $1 billion or more as of their most recent funding round — it’s clear that investors are still paying amply for unicorn equity.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

A decline in total unicorn fundraising is not a surprise. As we explored earlier this week, late-stage rounds are shrinking. That’s generally where unicorns fall in the fundraising lifecycle, albeit with exceptions, meaning that if late-stage rounds are getting smaller, it makes sense that unicorns would raise less capital.

Let’s review the data, compare where 2022 is heading in contrast to recent years, and then ask ourselves what a slower pace of funding for billion-dollar startups could mean for the IPO market. To work!

Let’s review the data, compare where 2022 is heading in contrast to recent years, and then ask ourselves what a slower pace of funding for billion-dollar startups could mean for the IPO market. To work!

Back to normal

As a former Crunchbase News staffer, I am more than a little familiar with the company’s public data dashboards. But new to me was a particular view showing how much capital unicorns raised in any particular year.

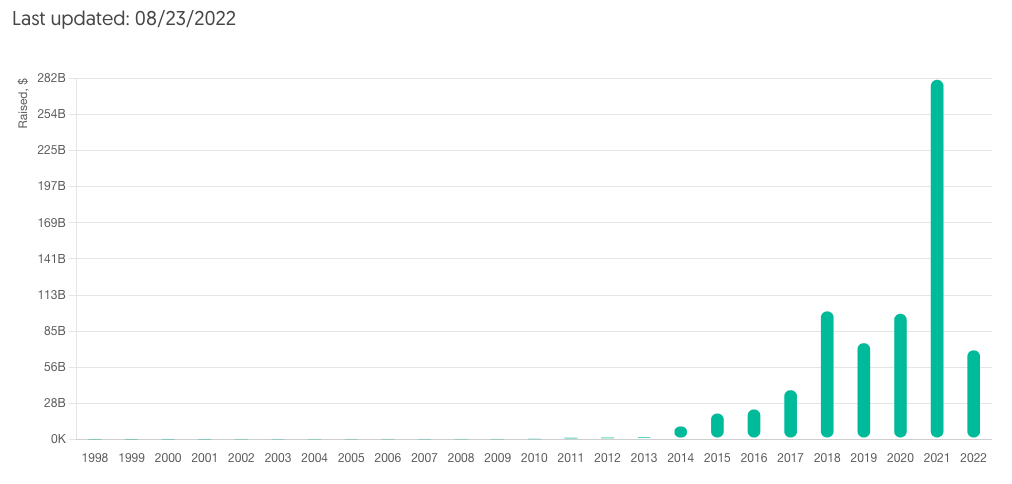

See if you can spot the year that doesn’t quite fit with the longer historical pattern:

Image Credits: Crunchbase

As you can see, capital raised by unicorns rose from effectively zero in the pre-unicorn era to an ever-rising total kicking off in 2014 and lasting through 2018. From there, a modest dip rebounded in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Recall that 2020 brought with it a sharp, short-lived recession that slingshotted back to bullishness in record time. (Tech companies, it turns out, are often recession-durable thanks to their software products proving critical for continued operation.)

Thanks to that bounce, 2021 nearly tripled the respective $101 billion and $99 billion that unicorns raised in 2018 and 2020 with a staggering $282 billion haul. That’s a figure that I doubt we’ll see beaten in some time. (Inflation isn’t that hot!)

This year, as of Tuesday, the unicorn contingent has raised just under $71 billion. If they maintain that year-to-date pace, unicorns are on track to raise about $110 billion this year.

That number could be a little high, given that the venture slowdown didn’t really start to bite until we were a little bit into the year. But even a $10 billion reduction in year-end totals would put 2022 flat compared to what had been the two best years in unicorn fundraising history before 2021 came around and crashed everyone’s historical data party.

Is a reversion to prior records a bad thing? Sure, if you wanted to raise $100 million at a $2 billion valuation with a 200x ARR multiple. Those deals, so we hear, are over. But provided that your unicorn is more secure in its revenue base, then it should be fine. After all, 2018 and 2020 were good years, right?

There’s an old saying that if you are accustomed to privilege, equality can feel like oppression. Well, if your main point of context is the 2021 funding market, sure, 2022 is likely a shock. But provided that you have a memory longer than the average fish, there’s nothing to be so scared about. Yet.

Things could get worse. Interest rates are rising, global growth is slowing, inflation remains an issue, and consumers around the world are dealing with water and temperature issues. Usually too much of one or too little of the other. There’s a fair chance that the global macroeconomic picture could soften further, and then the startup fundraising market really could change in tenor. But I refuse to cry about a return to investment cadences on pace to set records if you yank a single, anomalous year from the dataset. That’s just good eating.

One last thought: If the unicorn funding market does slow to prior levels, will that lead to fewer unicorn births? And, if so, does that mean that fewer unicorns would pile up at the gates of the private markets? Finally, would that situation imply that a return to IPOs could actually begin to thin the private-market unicorn herd by shepherding more behorned quadrupeds to public exchanges?

We could be seeing some early indications that the unicorn traffic jam is at least accumulating more slowly, which would imply some sense is returning to a market that at least in theory eats off realized returns not merely paper gains.